Story by Brandon Barrows

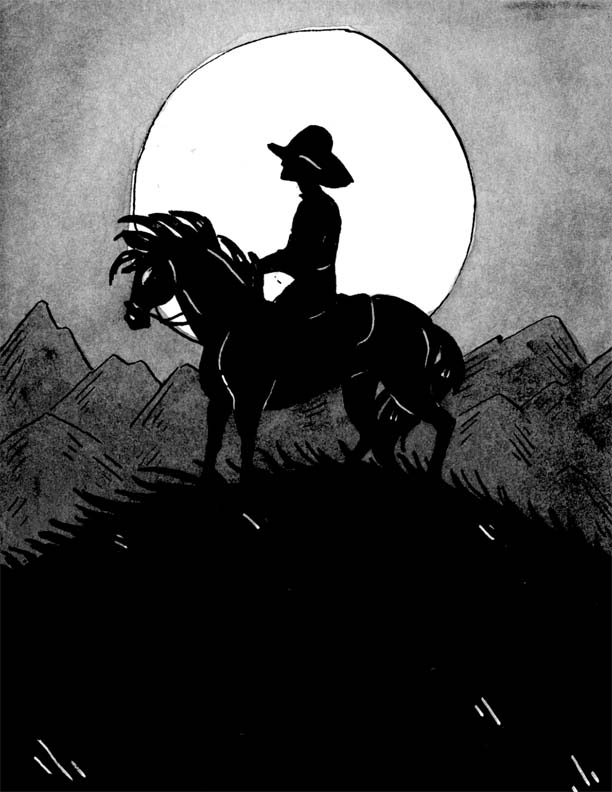

Illustration by Lee Dawn

I rode into Aldensville as the sun was setting, slouched low in the saddle. The sweat and dust from the trail formed a gritty paste that seemed to fill every pore of my body, making my clothing stick and itch, but I was too sore, too tired to do anything about it. The big roan beneath me was tired, too, but as we reached the junction of Main and Orleans Streets, I felt his pace quicken as he turned instinctively towards Len’s Livery, sensing food and water and a relief from his labors. I wished my own problems were as elementary or as easily solved.

I let the horse have his druthers, since we’d end up at Len’s sooner or later, anyway, but kept his pace down as we crossed town. Lights were beginning to come up in the windows of the wooden frame buildings that lined the street, and here and there a shadow appeared, seeming to look down on us as we passed. They had a right to their curiosity. Lord knew I had plenty of questions of my own.

The livery was only half-lit as we approached, old Len McCall scurrying to light the lamps when he spotted us. He raised a hand in as I pulled the horse to a stop and dropped from the saddle. “Evenin’, Ernie. Glad to see you back,” the hostler said. There was a question beneath the greeting, but he let it go unspoken.

“Take care of this fella for me, will you, Len?”

“Sure thing, but you should know—“

He didn’t have to finish the thought; I saw for myself what he was trying to tell me when three more men came around the corner, stepping out of the shadows they’d been half-hidden in. It was clear they’d been waiting for me, but I tried not to read anything sinister into it.

The lead man wasn’t the biggest of them, but he was the most imposing: below average in height, but thick and solidly built, he was draped in a suit of the finest broadcloth with a thin gold chain stretched across his chest. “Well, Marshal Farrar?” Mayor Matt Watkins asked.

The question might have meant anything, it was so vague, but that night in Aldensville it could only meant one thing: had I found Dennis Brody’s killers?

It was after seven in the evening. Ten hours earlier, Dennis Brody’s body had been found at Hangtree Crossing, less than a mile from town. Brody wasn’t anybody special, just another forty dollar a month cowhand, working the line for the Squared Oh, the largest ranch in the county. Alive, he was fairly anonymous in a town that was full of cowpunchers. Dead, back full of holes, and for no obvious reason, he was a source of fear. Back-shots meant bushwhackers and bushwhackers could mean anything. A lot of people were eager to put their fears to rest, maybe even to use the old hanging tree again, if it came to that. As marshal, it was my job to see that it didn’t come to it; that’s what Watkins had hired me for, after all, and he was within his rights to want answers. I just had to decide what answer to give him. I’d never yet lied him or anyone else in town, but there was a first time for everything.

“There were two of ‘em,” I said. “I tracked them into the hills then lost the trail.”

Yancey Frankes, a gangly, hawk-faced man of about thirty, pushed Watkins aside and snarled, “Is that right? I suppose,” he continued, turning towards the mayor, “that since Brody was my hand, I should have done my own tracking, seeing as your boy doesn’t seem capable of it.”

Frankes was the owner of the Squared Oh, and much of the best grazing in the valley, but despite being the richest man in town, he always seemed to have something to be unhappy about. For the past year or so, it’d been the homesteaders who’d moved into the land west of the Powder River, the dividing line between Frankes’s land and public domain. Whether he objected out of the traditional hatred between cowpunchers and nesters or because these particular newcomers were a group of six Chinese families come up from California, I didn’t know. I don’t suppose it matters, really, when one man hates another who’s never done him any wrong.

“Now, hold on, Yancey,” Watkins said, hands upraised in gesture meant to be placating.

“As a matter of fact,” Frankes went on, ignoring the shorter man, “I think we will do our own trailing, Ed, and we won’t waste no time poking around in the hills.” The third man, Frankes’s ranch foreman, Ed Lang, cracked an ugly smile.

“Meaning what, exactly, Frankes?” I asked, my voice sounding strained even to my own ears.

Frankes laughed – a brutal, mirthless thing. “Meaning that I think you’re just afraid to look in the right place since you gone all goo-goo-eyed over that little sod-buster chinkee gal.”

My right hand went towards the hickory grip of the Remington on my hip, but I pulled back before touching it and closed my fingers into a fist instead. Two easy steps put me within arm’s reach of Frankes and my fist arched upwards like a ball from a cannon, shot towards the heavens. It connected solidly with Frankes’s chin, sending up a muted crack that sounded loud in the stillness of the falling night. He stumbled backwards into Ed Lang and the other man’s arms going around his waist was the only thing that kept Frankes on his feet.

Blood stained the rancher’s lips, dribbling down his chin as he said quietly, “Prob’ly I deserved that, Farrar. A man’s business is his own, after all – but don’t let it get in the way of being our lawman. Brody never did harm to no one and killin’ him can’t be anything but a message from those damned nesters.”

“A message sayin’ what?” I wanted to know.

“That war’s comin’.” Yancey Frankes lurched away from Lang, pushed past him and disappeared into the darkness of the alley next to the livery. Lang cast a last look at me, Watkins and old Len McCall before hurrying after his boss.

I hocked and spat in the dirt to show my disgust. “That man’s a fool. Why would the nesters kill Dennis Brody? There ain’t more than thirty folks, including women and kids, among ‘em. Frankes has easily got that many hands and could call on more besides. Starting up with Frankes would be like signing their own death warrant.”

Mayor Watkins sighed and put a hand on my shoulder. “Ernie, you’re right, Yancey’s a hot-head and a bit of fool. But he’s also right about at least one thing: if you don’t find who killed Dennis Brody, there’s going to be more trouble. A lot more trouble, and this town just don’t need it. I don’t expect you to go out tonight, but could you at least go talk to those homesteaders, get a feel for whether they might be involved?”

I shook my head. “No man’s guilty ‘til it’s proven, and those folks out there have never given me any reason to suspect them of anything untoward. You know damned well why Frankes and his cronies hate them and it ain’t about what they’ve done so much as what they are.”

Watkins sighed, looked to McCall, who suddenly seemed to remember the bridle in his hand and lead my horse away into the depths of the livery building. Watkins turned back to me but didn’t meet my gaze. “Ernie, you know I don’t have anything against those people.”

“’Those people’, Mr. Mayor, have got the right to live same as everyone else in this valley. Whether you want to admit it or not, they’re helping build this community. How many ranches use the hay they raise? Or make bread with their flour? Just cuz they don’t dress or look or talk like the rest of the folks around here doesn’t make ‘em any less than you’n’me.”

“God damn it, Ernie,” Watkins swore. “You sound like a sod-buster yourself.”

“Maybe I should have been one,” I snapped, irritation boiling over. “It’s an honest life and I’ll wager it’s a damned sight less trouble than marshalin’.”

“Just… “Watkins faltered, seemed to be searching for words. “Just find the men who killed Dennis Brody and leave the sermonizin’ to the preacher!”

I had to smile to myself as the mayor turned and stomped off down the street. He was right, though, and so was Frankes in his way: I needed to find Brody’s killers pronto.

*

It was past the usual dinner hour, but Wright’s Restaurant still had lit windows and three or four customers could be seen scattered amongst the dozen tables. When I walked in the door, Annie Li, wearing blue, checked gingham and still looking bright and fresh despite the lateness of the day, looked up and showed me the special smile that I never saw her favor anyone else with.

I sat at a table by the counter and Annie hurried over, bringing coffee. “Ernie,” she said. “You’re late today.” Her English was good, better than most of her people’s, and I supposed that was the reason her father had put her up to getting a job in town, helping them build up a stake to get the family through the long winter that was coming. Whatever the reason, though, I was glad for it; I’d likely never have met her if she’d stayed up in the valley full-time, working the farm with her father and brother.

“Yeah, been out on the trail since this morning.” I leaned back in the chair, stretched my legs out beneath the table. It felt good to sit in something besides the saddle. I felt like I could climb into bed and sleep about twelve hours. Annie smiled again and that, combined with the strong, heady fragrance of the coffee, began to relax me. But it was short-lived as reality intruded on my thoughts again almost instantly. I wouldn’t really be able to relax until I’d put the present trouble to bed.

I’d lied to Watkins and Frankes earlier: I’d found a trail all right, but it didn’t lead up into the hills. It lead straight to the nesters’ little cluster of homes west of the Powder. It lead, in fact, right up to the front of the Li family’s home. I didn’t know Annie’s father or brother very well. Her father, Ho, didn’t seem to speak English much beyond ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye’. Her brother—whose name was Bai but went by Billy—I knew a little better. His English was good enough to sit and chat a bit when I’d visited their place, calling on Annie, but I really knew nothing at all of him as a man. Nothing but what Annie had told me: that he was frustrated with the meager life of a homesteader. I didn’t know if that was enough to drive someone over the edge. One thing I knew for sure, though, was that nobody, no matter how frustrated, was stupid enough to commit murder and then go straight home. When I’d arrived at the end of the tracks, though, there was no sign of either man, so I’d had no chance to talk to them about what had happened or what I’d found. I needed a way to talk to Annie and ask her if she knew what her father and brother had been up to the night before, see if they had a plausible alibi.

Annie was saying something I didn’t catch. “You hear me, Ernie? You all right?”

I smiled weakly. “Sorry, guess I’m more tired than I realized. What did you say?”

Understanding passed across her face. “You work too hard. You’re looking for who shoot that ‘puncher?”

I nodded. “Yeah, that’s right. Been a long day.” There was more I wanted to say, but the restaurant was no place to do it. “You going home tonight, Annie?” Since the homesteaders’ little community was a good distance outside of Aldensville proper, Annie traded off staying with Mrs. Wright, above the restaurant, and going home to help her father and brother, but the nights she did so didn’t fit any pattern that I knew of.

“Yes.” She glanced at the clock sitting on the shelf behind the restaurant counter, nestled between neatly stacked glasses and plates. “After we close up, I’ll go. Was supposed to go last night but got too late. Now, tonight, Mrs. Wright going to visit a friend and I don’t like to stay alone.”

That was a good idea the way things were headed, though I didn’t want to scare her by saying so. “I’ll drive you home, then,” I offered. “I’ll rent a rig from McCall and run you up.”

Annie’s smile grew wider. “I’ll like that, Ernie,” she said before turning towards the kitchen to fetch my supper. A tinge of guilt crawled around in my belly at the realization that it’d never occur to her I might have any kind of ulterior motive.

*

When we reached the crossroads where Dennis Brody’s body had been found, the moon had climbed high in the sky and was full enough that the slender rider cast a long shadow as he lounged in his saddle at the edge of the Powder River Road that lead up into the valley. Even in the pale light of the moon at a distance of thirty feet, both Annie and I recognized him instantly.

“Billy,” Annie said, a question in her voice.

“I come bring you home,” her brother said, by way of answer. “After the killing, this trail is not safe alone.”

So, he knew about Dennis Brody. It might have meant something, or it might have meant nothing at all.

Billy turned dark eyes my way and urged his horse forward, cutting the distance between himself and the buckboard in half. “Thank you, but I take my sister now.”

There was something in Billy’s manner that I didn’t care for; he’d never been overly friendly, but neither had I ever before detected the faint animosity that now hung in the air between us. I took a chance. “That’s thoughtful of you, Billy, coming to squire your sister home. Too bad you didn’t do the same last night. You or your dad. Annie tells me she planned to go home last night but didn’t end up making it out there.”

Next to me, Annie’s head turned. Her expression was somewhat confused. “Ernie, I told you, it was too late.”

“An,” Billy said roughly, using the girl’s birth-name. “I speak for myself. The marshal want to ask question, so ask.” His horse snorted and danced a bit beneath him, straining at the bit, perhaps sensing the rising tension.

“Billy, I was out at your place today and I couldn’t find you or your dad, so I’d like to know where you were, if you don’t mind.”

Something flickered across the young man’s face, something plain even by moonlight. He said, “Our cow break out of her stall in the night, and dad and me search for her.”

It was a flimsy excuse for a lie; that cow had been in the Lis’ corral when I’d been at their place. “Where were you last night, Billy?”

“Asleep. I go to bed early.”

“You a heavy sleeper, Billy?”

A look of confusion came upon him and I realized he didn’t understand the term. I tried to think of another way to phrase it, but Annie beat me to the punch saying, “Billy sleeps like a cat. The slightest sound and he awoken.” She turned to me, looking as puzzled as her brother had. “Why do you ask that, Ernie?”

I saw no sense in beating around the bush anymore. “Dennis Brody was shot right on this road sometime last night or real early in the morning. I picked up the trail of two horses pretty easy and followed it right up your front door, Annie. If Billy is a light sleeper, he’d have heard those broncs and woken right up.” I turned back to the young man, and added quietly, “Billy, you weren’t asleep at home last night and I know for a fact that cow was in your corral this morning.”

Beside me, I felt Annie stiffen, and her head turned from her brother, now as tense as a coiled snake, to me, then back again. “Ernie Farrar!” she gasped. “You call my brother a liar?”

“Annie,” I said, but wasn’t sure what should come next.

The girl stepped lightly down from the buckboard to the ground then crossed over to her brother’s mount. “I ride home with you, Billy.”

The young man offered her a hand and she swung nimbly up behind him, sitting side-saddle. She looked at me and said, “When you apologize to Billy, I see you again, Ernie. Until then…” She let it hang in the air as her brother swung his horse around and trotted off into the night.

*

I drove the buckboard slowly back to town, taking the time to think. I didn’t really believe that Billy Li and his dad were Dennis Brody’s killers, only that someone else wanted me to believe it. With Billy being evasive, though, and outright lying to me when all I wanted was to clear him and find the real killers, I didn’t know what I could do.

Halfway down Main Street in Aldensville proper, a crowd was moving in and out of the Longhorn Saloon – far more than was to be expected on a weeknight. Among them, I saw more than a few Squared Oh hands and some of the men looked liable to get rowdy, but when a few noticed my passing, a general settling rippled through the group. The looks I received weren’t friendly, but they were respectful. That was fine with me; a lawman’s job often meant walking alone.

“Practicin’ ridin’ a farm wagon, Farrar?” a voice called from the sidewalk, just out of the light spilling from the Longhorn’s batwing doors. Ben Thomas, one of Frankes’s long-time hands at the Squared Oh, lit a cigarette, the sudden glare from the match bringing his features into shadowed view. If Ed Long was Frankes’s right hand, Thomas was his left and as he stepped off the sidewalk, the look he gave me was neither friendly nor respectful. He grinned maliciously at me and tossed his match into the dirt in front of the horse’s hooves. I ignored him and kept the buckboard moving; savage laughter followed in my wake.

At the livery, Len McCall came hustling up to take charge of the rig. “That was a mighty fast trip, marshal.”

“Lots of people takin’ an interest in my comings and goings today, it seems.” I couldn’t keep the acid out of my tone.

Old McCall looked chagrinned. “Sorry, Ernie, but you know how it is. And you know folks’ll take even more interest in your doin’s if you don’t bring in whoever it was done for poor Brody.” He paused and looked as if he was trying to decide, as if he wasn’t sure he wanted to say what was still on the tip of his tongue. I climbed down from the wagon and McCall made his choice. He said, “There’s people sayin’ you read them tracks wrong, Ernie.”

“And what do they say was the right way to read ‘em, Len?”

“I guess I wouldn’t know about that,” McCall answered meekly. He looked as if he wished he’d never opened his mouth as he walked the horse and its trailing buckboard into the livery building. I followed and noticed that the stall where Yancey Frankes generally kept his big Appaloosa when he stayed in town was empty. There was no sign of Ed Long’s bay, either. Most of the Squared Oh crew was in town tonight, from what I’d seen at the Longhorn, but neither their boss nor his top man seemed to be around. That sent an uneasy feeling crawling up my spine.

“Any idea where Frankes got to after I settled his hash, Len?”

The old man waved a hand as if batting the very idea out of the air. “I don’t know a thing about that man’s doin’s, marshal.”

“But you sure seem to be keepin’ an eye on mine.”

Once again, Len seemed chagrinned, but this time, said nothing.

“Put my saddle on a good, fast horse, Len. I’ll be back in a minute.”

I left the livery, went up Orleans Street and back to Main, heading towards the Longhorn, but before I reached it, I hooked right into an alley between two storefronts. Keeping to the deepest shadows, I crept along the back of the buildings towards the rear of the saloon. Something was going on in town tonight, something that made the air seem thick with tension and aroused a kind of smoldering anger in my chest. Someone was trying to play games with me and I didn’t like it one bit.

I went in the back door of the saloon, walked down the dark, narrow corridor that lead to the barroom. At the doorway into the saloon proper, I paused, struck by a sense of wrongness. I could see that the room was full: men stood at the bar, or sat at tables, drinking. There was a passel of empty bottles scattered across the bar-top and on most every table. But there was no music, no card games going, no women in evidence – not even the usual commission girls who’d easily make their week’s wages pushing drinks to a crowd this big. Instead, the men were talking in small clusters, low-voiced. Eyes kept darting towards the front of the room, towards the saloon’s doors. Most of those I saw were either Squared Oh men or hands from ranches friendly to Frankes, all of them diehard cowpunchers who thought like Frankes did: that the range belonged to them and them alone. They were gathered together, all waiting for something, and I had a sinking feeling that I knew what it was.

I moved out of the doorway, putting a little more heft into my step than was necessary to ensure the hard soles of my boots sent up a clear sound against the varnished wood floor. Heads jerked in my direction and instant, pensive silence fell. I spotted Ben Thomas by the end of the bar, standing with two other long-time Squared Oh ‘punchers, and moved in his direction.

“Ben,” I said softly. “I’d like to speak with you outside, if I could.”

Thomas looked at his friends, on either side of him, then back at me and grinned that same, mocking grin he’d given me out in the street earlier. “I’ll do my talkin’ where I please, Farrar, and I’m plenty comfortable where I am right now.”

I shrugged, making as if it didn’t matter, and said, “Fine, then. Just tell me where your boss and Ed Long are tonight.”

The question hit home. The smile on Thomas’s face disappeared beneath a mask of caution. “How the hell should I know?” he asked.

“You know,” I told him, “because you’re all here waiting for them to ride back into town. It’s plain as day, so just tell me where they are so I can head off whatever foolishness they’re planning.”

One of Thomas’s friends snarled, “Better watch your mouth. There’s a lot more of us’n there are of you.”

I gave him a slow smile and rested my hand on the grip of the pistol at my side. “That’s certainly true, but who do you think’ll go down first if it comes to it?”

Thomas’s eyes flitted between my face and my weapon, his own hand inching towards the Colt Navy .36 hanging low on his thigh. “Go to hell, Farrar. I don’t have to tell you a damned thing.”

Burt Pickering, the owner of the Longhorn, chose that moment to intervene. Sweat beading his high forehead, big belly straining against a stained, white apron, he leaned forward on the bar and said, “Marshal, I don’t want no trouble in here.”

It was almost a plea, but it served well enough as a distraction – or so Ben Thomas thought as he went for his piece. His hand dropped to his holster as quick as a striking snake, but I was prepared and I beat him to the punch – literally. My fist snapped up and out, landing a solid blow on the man’s cheekbone, the sound deep and ugly as if something in it broke. Ben Thomas was bigger than me, beefy through the chest and shoulders, with a neck like a bull’s, but his guard was down, and he hadn’t expected me to use a fist when he was going for his gun. The surprise and the pain combined, and he stumbled backward, catching himself on the bar before falling, but only for a moment; it was like all the strength went out of his body as he sank slowly down to the floor.

I lifted the Remington from its holster, turned and trained it on the rest of the room. “I’ll arrest every last man of you for obstructin’ justice if I don’t get an answer to my question. Where the hell are Yancey Frankes and Ed Long?”

Pickering, probably the least-involved the man in the room, spoke up first: “They’re out followin’ the tracks you misread, Marshal Farrar,” he said sullenly. “They said they’d be glad to do your job if you weren’t willin’ or able to.”

A man I didn’t recognize stuck his head in the door at that moment, shouting with excitement: “They’re comin’ in! Yancey and Ed got the old man and the boy all trussed up and it looks like the gal’s taggin’ right along, too! We’ll get those damned nesters up in the old hangin’ tree whether Farrar likes it or— “and then he cut himself short, his eyes going wide as they landed on me.

“Or what?” I asked, voice soft, though I knew every man in the room heard me just fine. The man who’d been so excited a moment before ducked back outside and disappeared. I wasted no time following.

Out in the street, a small crowd had appeared, and word was spreading like wildfire as more people came out of homes and what businesses were still open at that hour. Up the street to the right, four horses approached at a swift walk. Yancey Frankes and his Appaloosa were in the lead; behind him came Billy Li and his dad, Ho, tied back to back, seated on the same horse I’d seen Billy riding earlier in the night. Ed Long followed on his bay, reins in one hand and a rifle, barrel resting against his shoulder, in the other. Bringing up the rear was Annie, riding in a wagon with three other Chinese homesteaders I knew by sight, though not by name.

A powder-keg was being built right before my eyes. I had to find a way to smother it before it exploded.

I stepped out onto the sidewalk then down into the street, putting myself between the growing crowd at my back and the newcomers at the heart of this mess. Surrounded, I never felt so alone in my life. I could only imagine what the Lis must have been feeling.

“That’s enough, Yancey,” I called when the men brought their horses to stop fifteen or twenty feet away from where I stood. I had to tread lightly, choose my next words carefully. I suddenly had the answer I’d been searching for all along, one simple enough that even a fool wouldn’t try to refute it. I was right in the middle of a potential mob, though, and if I didn’t disperse it quickly, it’d be guns doing the talking. “Let those men down from there.”

“Now that we’ve done your job, you mean to arrest ‘em and take the credit, Marshal?” Frankes said, a sneer in his tone.

“I mean to arrest someone, all right, but it’s not the Lis – or any other of the nesters.”

A murmur went through the crowd behind me and I heard someone—Ben Thomas, recovered from his trauma, it sounded like—swear loudly.

Annie Li hopped down from the wagon she’d ridden in on and inserted herself between me and Yancey Frankes. “Stop this! My brother and father— “

“Are gonna hang!” Frankes roared and at least some of the growing mob sent up an echo of agreement.

“Why?” I asked, giving the single word as much volume as I could without seeming to be shouting. I wanted every soul present to hear my conversation with Yancey Frankes. Gently, I pushed Annie towards the relative safety of the crowd.

“’Why?’” he asked, incredulous. “Because these slanty bastards killed my man, Brody, is why, and I’ll hang myself before I let a nester of any stripe get away with murder.”

“You lie!” Billy Li cried, finally speaking up for himself. “I saw! You kill the man Brody and I heard, too! I go to town to bring An home but I stop when I see riders and I hear your argument, about plan to fence off the water and drive us out! The man Brody say it will hurt everyone in valley, not just us and you can do what you want, but he won’t be part of it! That why you kill him, so he can’t tell anyone – and blame me, because you know I saw!”

A gasp went up among the gathered people and then whispers followed on its heels.

Billy’s eyes were wild as he turned towards me. “I ride around and lose them, then hide with neighbors who go get dad, keep ‘im safe.”

Yancey Frankes cackled and said, “Ain’t that a likely story, all? If it’s true, then how come we was able to follow that loopy trail you left—the one our esteemed Marshal Farrar says he lost sight of—from the crossroads right up into the hills and all the way around and back down to your place, nester? You left that sign clear as anything and all we had to do was follow it right to your door. That’s all the evidence I need to see to make sure you hang!”

The noises in the crowd intensified, threatening to boil over into violence.

“The men guilty of Brody’s murder will hang, all right,” I said, “but it’ll be due to the lie you just told.”

Frankes stared down at me, his brow furrowing beneath his wide-brimmed Stetson. I turned from him, faced the crowd. Mayor Watkins had, somewhere along the line, shown up and taken a place at the head of the townspeople. Directly to him, I said, “I have to come clean and admit I lied to you earlier, Mr. Mayor. The trail I found lead straight to the Lis’ doorstep, not up into the hills like I said. In fact,” I turned back towards Frankes, “it was too damned straight. Nobody’s stupid enough to commit murder and then go right on home, so before I came back to town, I spent some effort brushing that trail out entirely, both to give myself time to figure out who really done Brody’s killing and so no damned fool would follow that false trail and take it upon themselves to get ‘justice’ for Brody. The only ones who could have followed that ‘trail’, Yancey Frankes, were the bushwhackers who laid it!”

My eyes were on Frankes while I spoke and that was my mistake – I’d completely ignored Ed Long until I saw the flare from the muzzle of his rifle and by then it was too late. I felt the bullet slam into my right shoulder like I’d been hit by a train; it knocked me off balance, and I went to one knee. The crowd roared and began to scatter. I was dimly aware of Frankes going for his own gun as I tried to get my pistol from my holster with a left-hand cross-draw, but before I could, a second gunshot rang out, then a third. First Long fell from his saddle to lay silent and bleeding in the dust kicked up by the dancing hooves of his terrified mount, then Frankes tumbled from his horse, sending up a storm of curses as he cradled a bleeding hand to his chest. I turned and saw Ben Thomas standing on the wooden sidewalk, his gun drawn and smoking, a look of pure hatred on his bruised and swollen face – a look he directed at his boss.

Annie Li ran up, helped me to my feet and pressed a wadded-up handkerchief to the bleeding hole in my shoulder. Mayor Watkins and a couple of townsmen dragged Frankes to his own feet, the rancher keeping up a steady stream of swears over his mangled hand. Watkins slapped him across the mouth and hissed, “Quiet down! That hand’s the least of your worries! You’ll hang for what you done!”

Frankes jerked away from his captors’ grasp and took a step towards me, murder on his face, but Ben Thomas moved between us and pushed the smaller man back towards the mayor and his helpers, who took a firmer grip of the rancher this time.

Ben Thomas spat at his boss’s feet and said, “You lied to us, Frankes, and we almost did murder because of it.” He turned to me and said, “I’m sorry, Marshal Farrar. I never even thought… I’m ashamed.” It took a big man to admit when he was wrong and there were few bigger than Thomas in Aldensville.

“So should we all be,” the mayor added. He looked to where a couple of men were easing Ho and Billy Li down from the horse they’d been trussed to. Billy looked relieved. The old man did, too, but more than a little confused, as well. Without knowing what had been said, I supposed the whole ordeal must have been all the more frightening.

The mayor was saying, “It’s thanks to the keen minded levelheadedness of our marshal that justice was done here tonight and that a terrible mistake was avoided.” He moved to Ho Li, took the other man’s hands in both of his and said, “I’m so very sorry, sir, for what happened. You have my word that Yancey Frankes will get what he deserves.” The nester tried out a tentative smile and nodded his head vigorously.

Annie, too, smiled and leaned against me, helping me keep my feet. Through the layers of clothing between us, I could feel her trembling, and it had nothing to do with the slight chill of the night. Tragedy had been averted by a narrow margin and we both knew it. I wanted to make sure nothing like this ever again happened to her or her people. I thought about what I’d said to Mayor Watkins earlier about being a sod-buster myself. It’d been said in anger and annoyance, but I was starting to think maybe there was some truth in it.

“Annie,” I said, “Your brother and dad must have a time of it out there, working the farm by themselves. Maybe another body’s what they need. I was thinking maybe I might like to learn how to use a plow—“

“Hush,” she said, looking up at me, something twinkling in her eyes. “What we need is good marshal and no one is better than you.”

“Well,” I said through a smile that threatened to split my face in two. “You know what a good marshal needs? A good wife.”

“I think you’re right,” she said and snuggled just a little closer.

— ♦♦♦ —

END

The Devil in Disguise Part 3. By Nick Swain, Art by Sheik

Read the exciting conclusion of “The Devil in Disguise”. It had all gone south for The Man. This story will end in a blaze of gun fire. Who, if anyone, will survive?