Story by Anna Ziegelhof

Illustration by Bradley K. McDevitt

“Hello, funny horse,” my supposed little niece cooed into the misty twilight beyond my sister’s sitting-room window.

“What’s a funny horse?” I asked little Violet but then I remembered that my sister had told me to ask the girl only yes-or-no questions if I wanted an answer.

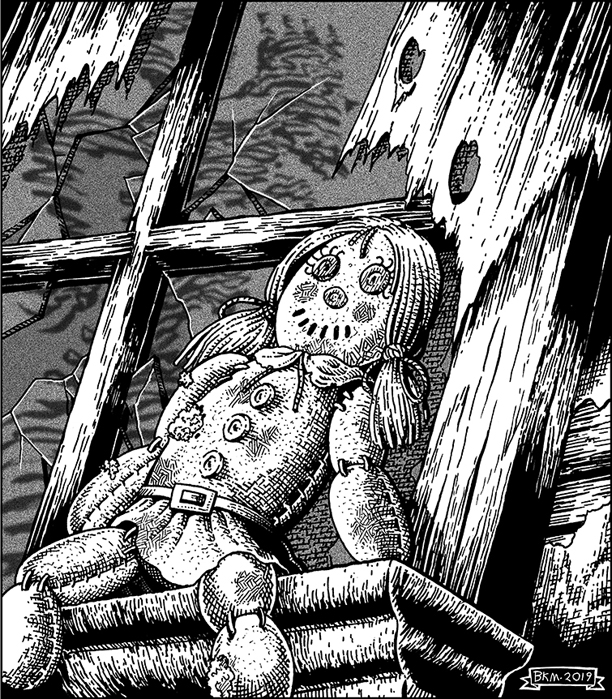

“Funny horse!” my supposed little niece repeated but then she thought of something vital elsewhere and climbed off the sofa under the window through which she had been peering into the fog of the darkening evening while marching her rag doll along the windowsill.

Being alone with my niece was better than being alone with an adult who felt like conversation was always needed, who felt like an explanation was needed. My niece couldn’t remember anything either. She couldn’t remember me. She didn’t explain. She just carried on.

My niece didn’t care when somebody said to her that her auntie had been very ill and wasn’t quite the same anymore. My niece didn’t know what “the same” was. So, we learned new things together. Since I was an adult, at least in appearance, she and I could be left alone together and so we explored the names for things and memories, from scratch. All, so long as we didn’t leave the house. But who would want to, in that dreadful fog?

Had I really been ill? Or was it a convenient lie to make a complicated situation less so?

Where had I been while I was so ill? In hospital? At home? At my sister’s country house where my first new memories were set?

What had the doctors said was wrong with me? A fever?

The answers, according to my sister, were too tiring for me and I would learn eventually.

Eventually, I did.

When it gets too quiet around a two-year-old, I was told, you had better check on them.

“No, Violet!” I shouted when I caught her in the entrance hall with her hand reaching up for the doorknob. The word “No” sometimes caused a bit of a crisis, so I ran to her and hugged her pre-emptively and explained.

“Explain things to her, she understands a lot of things,” my sister had instructed me.

“Remember?” I said gently, “Mummy said not to go outside!”

How conveniently I could blame my sister; how urgently I needed to convince her little daughter that her mother was the only reason we couldn’t go outside, that my visceral fear of the fog out there had nothing to do with it.

My sister bore my burden with patience and charity. Once a week, she guided me very gently from the quaint cottage’s doorstep to her conveyance. I could bear to be outside with her because my urge to hide my fear from her was stronger than the fear itself.

“I’m not frail!” I wanted to assert when she shuffled with me from the door to her carriage, and I probably did on occasion. I could walk. I could probably run. My body knew things. I couldn’t have been that sick for that long if I could still feel those tough little muscles bulging on the back of my arm.

But my sister guided me, one hand on me, always. She helped me up into the cab and closed the door behind me, gently.

I’m not frail. When I first remembered again, there were calluses on my hands. They had softened in the weeks since.

Once a week my sister drove me into town. She opened the door for me, she helped me down as if I were little Violet and escorted me into the offices of my psychiatrist, Dr. Hultgren, who listened to me muse about growing a new memory; I, reclined on his green velvet chaise, he behind his heavy brown desk, scratching his fountain pen across notepaper.

But even after weeks on his green chaise, old memories didn’t grow back. Only new memories stayed, of days filled with jigsaw puzzles and Violet in the country house by the foggy meadow.

Upon our arrival at Dr. Hultgren’s offices, my sister would step back graciously and grant me some privacy. So, she was not there when I met Dr. Abigail Allen. She might have dragged me away. She might have prevented my meeting her.

That day, an unfamiliar voice called me into Dr. Hultgren’s office.

“Where is Dr. Hultgren?” I asked the tall, severe woman who met me at the door to his office, in his place. Dr. Abigail Allen tutted. She held my hands.

“What happened to your hands?” she said and investigated them with intensity. She turned my hand to show me exactly where it was soft instead of callused. “How are you going to go back to work?”

“Dr. Hultgren is treating me for amnesia. I do not know what my work used to be,” I explained.

I was confused. Dr. Abigail Allen seemed to know what my work had been. Dr. Hultgren had not told me. My sister had not told me. My sister had left me to survey my body and extrapolate from muscles, calluses, and scars. And I had had no explanation. I couldn’t have been a field hand, given my sister’s standing in society.

I found Dr. Abigail Allen to be quite odd and I felt reluctant to continue my sessions with her while Dr. Hultgren was away or indisposed.

“Come in,” Dr. Allen said pleasantly, and her earth-colored lace gown swept Dr. Hultgren’s office floor on her way over to his chair behind his imposing desk. I followed her, though hesitant, and took my usual place on the moss green velvet chaise.

“Your sister, Mrs. Eleanor Bridges, introduced you to Dr. Hultgren?” Dr. Allen asked me. A statement and question.

“Yes,” I confirmed. She had sounded so suspicious. “I was in no shape to seek out a doctor for myself.”

“Do you have the impression that Dr. Hultgren has been a great help on your way to recovery?”

“He’s a wonderful man,” I said to be polite.

He was doubtlessly a wonderful man but my recollection of anything that had happened before I woke up in my sister’s pleasant country house one morning, weeks ago, was still a plain white, impenetrable marble floor: nothing shimmered, hinted or glittered there of my old life.

“The thing is,” she said and stood up and came to sit next to my outstretched legs on the green velvet chaise. I shrank away from her, startled at so much familiarity.

She looked at me with her strange purple eyes. She bored me with them. She glared. She tried shooting sharp glances straight from her brain into mine. She looked desperate to make me remember, all at once preferably, not easing, not gently, not baby steps, bits of progress here and there as my sister had always reassured me was the way forward.

“The thing is,” she repeated and looked at her hands. Then she took my hands and patted them and glared at me again, “we are not quite sure Dr. Hultgren is trying very hard, perhaps according to your sister’s instructions to him, and we need you to come back to work. This right here,” she ran her thumb across my palm where those calluses had slowly disappeared since I had been holed up in my sister’s cottage, “mustn’t happen. It is coming closer too rapidly.”

“Forgive me, I don’t…” I frowned at her. When you can’t remember your life, people say incomprehensible things to you a lot.

“Your sister has been keeping you under lock and key, Soph. She is a lovely woman, but she has withdrawn from our struggle. She doesn’t realize the importance of your work for our community. The only way we could approach you was here, by causing Dr. Hultgren’s regrettably being indisposed and failing to inform your sister that you would meet me instead. Your sister does not seem to comprehend the urgency of the situation and the dire threat we are under.”

Something tickled in my brain. But maybe that was just normal when somebody mentions a threat and an urgent situation. I didn’t know what my personality was like, before. I knew that under my sister’s care I had been made to rest a lot. I had been reminded not to exert myself, not to think too hard. But my body told me a different story. It did tell a story of exertion, of rigor.

And now, her words triggered a feeling – not quite a memory but a realization. When somebody triggered my brain by using the word ‘threat’, a pushing, nagging, dragging feeling surged up inside me. A threat made me want to spring to my feet. It made me want to grasp… something. I closed my eyes on the green velvet chaise and my muscles remembered for me. My hands closed around an imaginary staff. Well worn to the shape of my grip. Right hand on top, always.

“Sophia fights right hand on top!” a faint girlish voice reached me through the fog.

I opened my eyes.

“Tell me everything you know!” I demanded and the voice that came out of my throat felt like my own voice for the first time since I had woken up in my sister’s house. No gentle cooing, no ‘you’re too kind’, no ‘what’s this, Violet?’

“All at once?” Dr., Abigail Allen was in doubt. “That’s not the way we usually do it, but then, we have lost a lot of time in your case.”

“Start at the beginning!”

She smiled and offered me her hand to shake. No gentle patting and holding: a firm clasp. We were in business and suddenly, all at once, I felt healthier.

“Doctor Wrenworth, welcome back!”

“Doctor!”

“I see we’re going to have to start at the very beginning,” Dr. Allen sighed.

“Why didn’t my sister tell me? My name is Doctor Sophia Wrenworth?”

‘Oh, dear Soph, oh sweet Soph,’ Eleanor had cooed.

“Doctor of what? Medical? Philosophy? Jurisprudence?”

“Urban planning,” she chuckled.

“Excuse me?”

She shook her head. She offered me the chair across from Dr. Hultgren’s desk, rather than the reclined chaise.

“Dr. Wrenworth, you used to joke that that was your occupation: urban planning. In fact, of course, your expertise is in Psychology, Parapsychology, sub-field Cryptozoology, ever since the threat became so real…”

“Slowly. From the beginning. I have amnesia. So, leave out the allusions and explain to me in plain words what you know. Then tell me how I can help with the aforementioned threat.”

“You are Doctor Sophia Wrenworth, senior administrator in the department against urban decay of our municipality. Your preferred weapon is the staff.” Dr. Abigail Allen rose from Dr. Hultgren’s desk and produced a rod from the pocket of a long coat that was hung up in a wardrobe behind her.

I stood up from my chair, in something akin to recognition. Dr. Allen handed me the artifact as if it were something truly precious. I closed my hands around its handle. My hands fit perfectly. I let my eyes follow the staff from its handle towards its tip. It turned into something exquisitely crafted, a blade so shiny and sharp it would have caused you to bleed out before even noticing pain from the cut it had given you.

I turned away from Dr. Allen for safety reasons and swung my staff, lunged forward, and stabbed the blade into the back of the green velvet chaise. My body remembered exactly how to move and how to breathe. I extracted the blade. I telescoped the staff back to its smaller size, designed perfectly, convenient to carry; I slid it into my holster, or, I was about to when I remembered that I was not wearing it. She nodded, smiled, and handed me a belt that I promptly donned and then put up my weapon.

“So far so good,” I heard myself joking.

A satisfied smile played around Dr. Allen’s lips.

“Now, tell me, what are we hunting out there?”

“Whatever is hunting us, dear Sophia. Finding out exactly what it is a persistent item on our research agenda.”

She turned around and extracted from the same wardrobe from which she had fetched my weapon, a large canvas, rolled up neatly. She placed it on the desk in front of her and unrolled it.

“This is our town,” she explained without my having to prompt her and remind her yet again that I was conscious of very little that others were taking for granted. “Our quaint, rural town. As little as five years ago.”

She turned and produced a second map, slightly translucent. She superimposed the second map over the first.

“Our town, circa around the time you were declared injured in action.”

I didn’t understand the implication quickly enough. Something inane slithered out of me, some No Shit Sherlock statement I’d almost rather not repeat, something like, “Look, it’s shrunk!”

Dr. Allen looked at me and the tight skin around her eyes told of a battle that had lasted too long. With a compass and a ruler, she measured in front of me the exact dimensions of the catastrophe.

I pointed to the schematic representation of houses, an entire neighborhood that fell in the gap between the old map and the new, smaller one. Dr. Allen shook her head.

“Devoured,” she stated.

“What’s there now?”

“Just the fog.”

“Which one is my sister’s house?” it suddenly occurred to me. I had not been paying attention to roads and directions, it had seemed too overwhelming a chore to add a map to my failing brain. I had not left the house much anyway.

Dr. Allen seemed to weigh options: tell me, not tell me. But even the fact that she was contemplating whether she should allow the devastation to come over me, told me that there was devastation. She finally pointed to a house on the border of the frayed edge. Encroaching. The ragged edge that swallowed the map, the neighborhoods, meadows, and houses were so close to the little cottage that had held my life, my sister’s life, my niece’s life, so comfortably for the past weeks.

“What appears instead of the houses? What is beyond the border? What’s in the fog?”

It was another question Dr. Allen was reluctant to answer.

“A nameless horror beyond description.”

“Like, what? Nothing? Teeth? Tentacles? I must know!”

Dr. Allen grasped her strong hand around my arm and glared intensely at me.

“You tried. You approached the border. You lost your mind. Now, that sometimes happens in our line of work, but this time your sister did not allow us to recover you.”

I nodded. It was reassuring that despite losing my mind to a nameless horror beyond description, my personality and inclinations seemed to have remained with me. My sister must have known that I would have rejoined the fight. She had decided for me and kept me and my mind soft and docile, in the fog.

My finger found the road on the map, the one road leading away from the shrinking circular confines of our city. It did not seem to be affected by the eating, fraying, burning of the map; it led away from our city and off the edge of the map on the table.

“Where does it go?” I whispered, to myself. “Where might it take us?”

Dr. Allen just nodded in agreement with something I had not yet said out loud.

I shook her hand firmly when I departed, an unspoken promise to use the clues she had given me, to become useful again.

I hid my holstered staff from my sister who picked me up after my session and drove me back to her cottage. I sat on the sofa under the window and peered into the late afternoon fog.

“Eleanor,” I asked innocently, “is it ever not foggy?”

Eleanor’s laughter peeled through the cozy room.

“It’s just the season, Soph. Just wait until you see the spring! Such beautiful blossoms!”

“Eleanor,” I asked, removing the innocence from my voice, “if you let this season pass without taking action, what will be beyond the fog?”

A jolt went through Eleanor’s spine. She sat up straighter and stared at her needlework with more intensity. She was not about to respond, but my little niece Violet, superficially engrossed in play with her rag doll, gave an answer with a poetic timing that was haunting and beautiful at the same time:

“Funny horse!” she exclaimed.

She dropped the doll and climbed up on the sofa next to me. Her little body rocked against mine as she scrambled along the soft cushioning on her chubby legs. “There, there!” she said and jabbed her tiny index finger against the windowpane.

“Now, now, Violet,” my sister cooed, much recovered from her instance of suspicion that I might have remembered or learned. “You know that’s just a story from your picture book. Now, you mustn’t alarm auntie Sophia.”

The insinuation that I should be alarmed outraged me, I found. I rose to my feet. I pushed my gown aside to reveal my belt, my holster, and my staff to my sister.

“You remembered,” she breathed, and her needlework dropped into her lap. Then she regrouped her countenance. “Not in front of the child.”

We met in the adjacent kitchen for a bout of dangerous adult whispering.

“I met with Dr. Abigail Allen. I do not remember but I feel the importance of my work in my bones. You are in danger and I am equipped to help. Why would you refuse that?”

“You are helpless!” my sister whisper-shouted at me. “We are all helpless against this. The best we can do is to wait and to pray.”

I was just about to disagree respectfully when Violet’s amused shout came from next door. “There, there! Funny horse!”

I didn’t hesitate. I rushed from the kitchen to the front door and opened it wide. The fog wafted around my ankles and into the foyer. My fear was with me immediately. But I moved one hand to my holstered staff, and I exited the cottage softly.

I allowed the image in front of me to resolve until I was, coolly and analytically aware that I was indeed staring at a nameless horror beyond description. It approached me through the undulating white patches of the fog.

“Hello, funny horse,” I said to the horror out there, imitating my little niece, my little Violet with no preconceptions and no descriptions. I drew my staff. It rested in my hands, safe and strong.

“Sophia fights right hand on top,” I remembered my sister saying with clarity, in our childhood, witnessed by our parents. Eleanor fought left hand on top. I remembered that in the beginning, our community had fought together. I remembered what had happened to our parents. And I knew that once the strongest fighters and most resilient thinkers had passed on, people had started surrendering to the horror, as my poor sister had now, and only very few of us remained, hunting, fighting.

I held the creature’s empty-eyed glare from its sinewy equine skull, skinned to reveal pulsing veins and brown flesh. It approached me on its unnatural number of legs that were too muscular to be insectoid, too multi-jointed to be mammalian.

I remembered that in insecto-mammalian horrors with a chitin exoskeleton the staff had the best chance of penetrating the infinitesimal gap between the overlapping breastplates that protected a black quivering heart.

I focused and aimed.

I lunged toward the horror and inserted my sharp blade neatly between the creature’s breastplates.

The horror let out a screech that might have made the sanest man go mad if a man had been around to witness it. The creature stumbled over its many legs. It fell from its great height. Its black blood oozed from between the plates of its armored skin where thick black hairy stubble grew from gaping pores.

The creature landed awkwardly, sprawled across my sister’s driveway, and breathed its last.

I held my stance, my staff at the ready. I remembered to wait the appropriate number of seconds to verify its death. Satisfied that I had made another one-stab-kill, I reached for my communication device and paged Dr. Abigail Allen to assist me with the autopsy.

After Dr. Allen and I had photographed, recorded, and described every inch of the nameless horror’s revolting body, we dissected it and filed it away in the department’s archives for future reference.

“Please!” Dr. Abigail Allen made an inviting gesture. “Your turn.”

My questioning look must have reminded her that I hadn’t quite recovered from losing my mind.

“After we describe it in great detail, we name the horror,” she reminded me patiently. “Would you like to do the honors?”

“Funny horse,” I said promptly. “Not my idea.”

We washed our hands and wiped sweat from our brows. Then we returned to the map table in the department against urban decay and observed the undulating fog displayed there around the edges of our town.

“You’ve exterminated a sizeable horror,” Dr. Allen sighed and pointed out how the fog had receded ever so slightly right there, around my sister’s cottage.

“Not sizeable enough,” I stated with regret and cast a worried glance at the edges of our shrinking town. I was interrupted in my despairing by a faint knock at the door to the mapping room.

“Enter!” Dr. Allen invited. It was my sister’s red corkscrew curls I recognized first when she peeked into the mapping room.

She entered and stood, stepping awkwardly from one foot to the other under Dr. Allen’s critical glances.

“Mrs. Bridges,” Dr. Allen greeted her.

“The fog has cleared a little bit around our meadow,” my sister reported. “Maybe it was wrong of me to keep Sophia away from her work. I was worried, what with our parents and my husband… I remember now that I used to be a fair fighter. Might I possibly join your ranks?”

With an inviting gesture, Dr. Allen asked my sister to approach the map table. Dr. Allen’s finger traced the road– enveloped by fog on both sides but clear in the center– our only way out.

“We are contemplating another attempt at traveling the road to beyond the map.”

My sister Eleanor looked uncertain but determined to hide it. She nodded.

“To recruit,” I added.

“There aren’t enough of us left in here,” my sister murmured.

“Yes,” Dr. Allen said, firmly, facing our truth straight on.

“I must take Violet with me,” Eleanor declared.

Dr. Abigail Allen opened one of the flat drawers of her weapons chest. Thoughtfully she selected a weapon that would fit the hands of a two-year-old. She handed it to Eleanor. Dr. Abigail Allen also selected a convenient child carrier from a wardrobe.

“We will carry her if she ever gets tired. The road might be longer than we anticipate.”

If Eleanor felt a pang of yearning for her quaint old life that she had just signed over to the department against urban decay, she didn’t let it show.

In the misty evening twilight, Eleanor and I took Violet out behind the house. We stood by the edge of the foggy meadow and taught her how to aim her little staff.

“Here’s one now, Violet!” Eleanor would tell her.

“Funny horse!” Violet exclaimed with glee, no names other than those of her own invention and no descriptions available to her yet, and she sunk her little staff with delightful ease and skill between the creature’s chitin breastplates.

“Very good work!” I lauded the child and the next morning, Dr. Abigail Allen, my sister Eleanor Bridges, my niece Violet Bridges and myself, Dr. Sophia Wrenworth, set out to travel the last remaining road.

We did not know where it would take us. Fog bore down upon us left and right, the nameless horrors were perched in it, out of sight, but never out of mind. Before us, the road stretched ahead, into the distance. It would lead us off the known map from where we would recruit help and return to slay the nameless horrors beyond description in the eternal fog.

— ♦♦♦ —

END

Next Week:

Clark’s Boy Part 2 By Brian Spiess , Art by Toeken

Clark’s Boy Part 2 By Brian Spiess , Art by Toeken

Danny had always lived up the mountain with his father. It has always been the two of them. His father admonished him to never go into town. Now, his father was gone and Danny had no choice…