Story by Cynthia St-Pierre

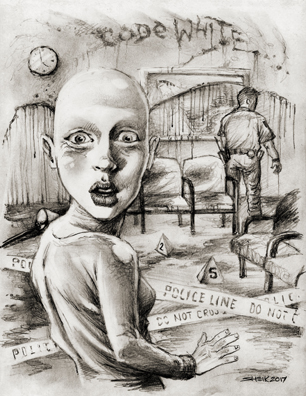

Illustration by Sheik

Pumped-in music distracted and soothed me until the general hospital intercom interrupted with a Code Blue.

I hate when that happens. It means a cardiac arrest or another medical emergency.

Usually the code location is nowhere near me, but this time it was right here in the Cancer Centre.

“1st Floor. Radiation Patient Waiting Room.”

Earlier, fifteen or so other cancer patients came and went while I was waiting exactly there. I hoped it wasn’t the dear senior I was talking to just before I was led in here. He’s beaten cancer twice before but now he’s back with most of his ear cut off and the rest of it, including surrounding tissue, flaming red in anger at the series of radiation treatments that are supposed to save him—again.

“Code White,” continued the female announcer with an Indian lilt. She sounded like my medical oncologist, who gave me a loving hug of encouragement at each chemotherapy follow-up appointment. It was not her on the intercom, though. “Cancer Centre. First Floor. Radiation Family Waiting Room.”

Now it’s a Code White? Code White means a disturbance.

“Code White,” she repeated mere minutes later, her voice calm. “Cancer Centre. Lobby.”

I calculated, Family waiting room to lobby, the Code White is leaving, thank God, because I’m not supposed to move a muscle and if I do, the giant robot that’s inching around me, clicking and buzzing and beaming radiation at me from different angles, will zap my lung instead of my right breast/underarm area and then I’ll be in real trouble.

After a few minutes of intercom quiet, giving way to pure Musac, during which I couldn’t help but imagine a poor fellow patient losing his battle with The Big C right there in the patient waiting room and then a family member going berserk with heartbreak in the family waiting room, I finally heard, “Cancel Code White.”

I breathed a sigh of relief, and then prayed my deep respiratory movement did not freak out the robot.

One of my technologists, who was monitoring me on a computer in the office just outside the radiation pod, broke in on Barry Manilow’s easy-listening “Mandy” and asked if I was all right.

“Sure,” I said. Relatively.

What really happened? I wondered but didn’t ask. And who was the Code Blue?

When the robot finished, both radiation technologists re-entered the room, lowered me to the ground and unstrapped me. I shrugged back into my gown, thereby covering up my own mutilated body part (thank God I still have a boob), and we exchanged a few pleasantries about the upcoming weekend as if life was a freshly-picked, warm-from-the-sun, plump and fuzzy peach.

“Enjoy the concert,” I said to one of them. “See you Monday,” I said to the other. We all get weekends off, you see.

“Yeah, have a good one,” I heard over my shoulder as I headed out past the gate that warns Do Not Enter from the other side.

I couldn’t help but notice a uniformed policeman in the hallway, but since I was half naked, I figured it was best to get changed into my clothes rather than venture into the Radiation Patient Waiting Room to see what happened.

After retrieving my clothes from the locker and changing inside one of the many change rooms, I dumped my used gown into the proper bin and headed to the waiting room. I expected to learn some poor patient had had a heart attack. I didn’t expect to see blood.

Soaked into the carpet and into upholstered chairs and splattered on the wall.

Moreover, I really didn’t expect the two entrances to the waiting room to be blocked off with crime scene tape and crime scene technicians—or some such—to be working within.

Right then I was thankful my sense of smell is still diminished (side effect of chemo) in case there was a coppery scent to this scene like I’ve read about in books. I swallowed hard and hurried on.

I did sort of figure that receptionists and volunteers would be huddled in discussion in the outer Radiation Family Waiting Room.

There, patients continued to fill out forms at computer terminals. Radiation treatment must go on, after all. But fewer eyes were trained on the flat-screen TV mounted in a corner and more were darting around trying to pick up whatever information they could about what happened.

The atmosphere in the Cancer Centre was charged with a new toxin.

Not corrosive chemo drugs. Nothing radioactive.

It was fear that betrayed itself in hushed and overly excited words.

Honestly, I don’t need the burden of more bad news, so what made me sit down beside a fellow patient anyway? I knew she was a patient and not a family member because her hair was just growing back, like mine.

“Do you know what happened?” I asked.

I was not acquainted with this woman I was addressing, but we’re a friendly community, we cancer patients. We’re bonded by the common experience of a disease we had no idea was so damn prevalent until we started coming here regularly.

“Bits and pieces,” she responded.

I raised my eyebrows…well, my non-eyebrows. A universal sign for “Please continue.”

“Seems a patient was shot. A woman.”

Shot? This seemed ridiculous to me. Cancer patients look and feel half dead, so I could almost see one of us doing our self in and getting it over with, but it was really, really damn hard to imagine someone killing someone else in this shrine to keeping people alive. Of course I didn’t say this. Instead I asked, “Do you know who?”

“No.”

Ah, I picked the one cancer patient who doesn’t elaborate. Most of us compare diagnoses, discuss treatments, exchange coping mechanisms, news and pleasantries at the drop of a hat. Companions on a lifeboat type thing. However, I understand that some of us can’t share any more trauma and still stop off at the grocery store for paper towels, whip up egg salad sandwiches on the kitchen counter for lunch, and put kids to bed at night.

“Explains the Code Blue,” I muttered. Then I couldn’t prevent myself from asking, “The woman die?”

“Think so.”

“What was the Code White?”

“The gun person.”

I shivered and I couldn’t blame it on a side effect of cancer treatment. “Gunman?” I attempted to specify.

“Who knows? Wore a baggy gown, one of those medical cappies and a surgical mask.”

“Got away?”

“Yup.”

“Geez!” I said.

She shrugged and slumped further into her chair.

I get it.

I pulled myself up and said, “See you.” And probably I will. I still have 20 more consecutive weekdays of radiation left, so I’ll be back.

It was a relief to get out of the building, disturbing enough on a regular day, but tack on a shooting…

My effort for this day was done. I drew in two lungfuls of fresh air and headed to the path that follows the waterfront all the way to Main Street and our apartment above the store.

I’m grateful that my dear half-sister Anne is looking after our design business, Beautiful Things, solo these days.

Sadly, simply looking after myself has become my part-time job. Who knew how time-consuming cancer treatment is? Walk to this appointment (I walk like a toddler), fill out this form, wait here, remember to ask these questions, make sure you set up your next appointment, fill your prescriptions, take your pills at the right times on the right days, and whatever you do, keep each $2,000 syringe of Neulasta in the fridge.

Once I forgot.

And later panicked, of course.

Is it poison now?

Will I have to skip it, which will lead to total immune system breakdown?

Will my insurance company pay for a new $2,000 syringe?

Which begged the question: Do I have time to order a new one before I’m injected?

Lucky for me, the number of hours the syringe lingered on the counter was deemed to be within the general realm of non-lethal.

Anyway…the leaves on the trees along the pathway were changing colour. They change earlier up here than they do in Toronto, and there are more gold and less red hues.

The breeze from the lake caressed my face. Gravel crunched under my feet. Seagulls squawked overhead. The blue of the sky was miraculous.

I’m one of the lucky ones. I have an amazing husband, who has stepped up like a champ, and whom I have never loved more. He has shown me who he is—exactly who I believed he was when I chose him.

I am grateful.

I thought of my new friend Julie, who is going through cancer treatment as well. No husband to hold her when she just can’t take it anymore. Michael died of a heart attack years ago. She found him lying on their living room carpet. Since then she has raised their son and daughter to adulthood on her own, barely making ends meet. She has no private medical insurance so a bunch of us got together to raise funds to help her with medical expenses.

I climbed the stairs to the piece of paradise I share with hubby Karl.

I inserted my key. I pushed in our door. My mouth flew open in happy surprise and I said, “You’re home early!”

“Come sit down. I’ll make you some herbal tea,” hubby said.

Herbal tea? Uh-oh.

I turned toward the living room and sat down on one of our two facing couches. Karl came in and set a pastel blue teapot and two empty cups on the coffee table. Then he sat down beside me.

“An incident at the Cancer Centre happened while you were there,” he said.

“I know. What happened exactly?” Karl gets the inside scoop because he is Chief of Police.

He took my hand. “Honey, I’m afraid you know the victim.”

Shit. Shit. Shit. Shit.

“Your friend Julie.”

— ♦♦♦ —

An additional shock was finding out mere days later that Julie didn’t have cancer at all.

“What? The Cancer Centre courtyard was where I met her,” I argued. I tried to think rationally but all I could feel was my heart speeding up in my chest. “She was totally bald.” This also works as proof of cancer because it’s safe to say that, in women’s fashion; bald is not the new black.

Karl only nodded.

“Julie always chatted up a storm. Listen,” I continued, “I know everything about her tumour—Stage IIB, invasive ductal carcinoma, 2.2 cm, both estrogen and progesterone receptor positive, lymph nodes engaged. Karl, we shared our hatred of Docetaxel!”

The last of my energy petered out.

“She was on cancer forums on the Internet,” I added weakly. “Remember that fundraiser her friend Jennifer threw that we all attended?” I was grasping at straws now.

“Of course I remember.” Then Karl suggested in his most comforting voice, “Julie might have convinced herself that she really did have cancer.”

“How…why would she do that?”

“Money.” He read my expression. “Sympathy maybe?”

I considered these possibilities for a minute. I wrung my hands.

“You know, when I first learned that there was a shooting and that the victim was one of us, I couldn’t figure out why anyone would kill a cancer patient.” I looked up at Karl then, my forehead still scrunched with incomprehension. “But if Julie really was faking it, if she was pulling on people’s heartstrings unnecessarily, I think that could possibly speak to motive.”

— ♦♦♦ —

Of course Karl and I were present at Julie’s funeral. Whatever the circumstances, the end of her life was a tragedy.

After the ceremony, I stepped outside to explore the lemonade and brownies set on folding tables covered with vinyl on the lawn behind the church.

When I caught Julie’s daughter momentarily alone, I said, “I’m so sorry about your mom,” and I meant it wholeheartedly.

“Thank you.” Melanie brushed away a trickling tear. “Thank you for coming. You’re…?”

“My name is Becki.”

“I should have remembered.”

“Not to worry. You met a lot of people at the fundraiser. You can’t expect to remember us all.” Geez, poor thing, she just lost her mom.

“So many people declined to be here when they heard Mom wasn’t really sick.”

I had to admit it wasn’t hard to imagine that family and friends were having a hard time overcoming an enormous sense of betrayal. “Funeral services are as much for family and friends as they are for the deceased,” I pointed out.

Melanie leaned in a little bit conspiratorially. “You know what’s weird?” she asked, her voice barely above a whisper. “Even if Mom’s cancer wasn’t real, it brought our family closer together. John… You know my brother?”

“Yes.”

“I’ve never seen anything so beautiful as when he, tough guy, sat Mom down on a stool and ever so gently cut off all her hair and then shaved her head.”

“Exactly what all the pamphlets recommend before hair falls out on its own.”

John himself joined us. He must have overheard part of our conversation because he clarified, “We didn’t know Mom was running a scam.”

“Of course you didn’t,” I confirmed.

He put his arm around his sister. “Melanie dropped her own life to be Mom’s caretaker. She cooked. She cleaned. She shopped. She did laundry…”

“A friend of Mother’s drove her over and over again to the Cancer Centre,” Melanie added.

That would be Jennifer.

“Dropped her off and picked her up again hours later,” John explained. “But apparently Mom never saw a doctor there.” He shook his head. “No medical records.”

“I guess she just spent the time wandering around and talking to people,” I said. “Sometimes grabbing a bite at the cafeteria.”

Eating at the hospital cafeteria in itself suggests a mental disorder.

I tuned back in to hear Melanie saying, “Just like you and so many other caring people, John and I also contributed toward her ‘expenses’.”

Poor kids are apologizing on their mother’s behalf.

“It’s a sad affair,” I assured them. “She fooled us all.”

A few minutes later, when I saw Karl motioning from the back of the church, I offered them hugs, told them goodbye and said, “My condolences again.”

— ♦♦♦ —

A few days later, Karl told me, “The Canadian Cancer Society claims donations are negatively affected by cons like the one Julie was running.”

“A negative backlash, yes, I can understand that, but you can’t tell me that cancer frauds generally end in murder!”

“No, most cancer fraudsters are prosecuted not executed. What I want to know,” Karl said, “is how you managed to tip us off about who committed Julie’s murder, considering the huge pool of suspects: family, friends, and contributors to the fundraiser… Anyone could have gone to the Cancer Centre with a gun.”

“I figured I was the most likely candidate.”

Karl’s eyes popped. “What? You? Why?”

“Because I actually did wake up in a surgical recovery room gasping for breath. Because I really have sobbed all night for the pain. Because for months now I can barely put one foot in front of the other. Because I have no freaking hair anywhere on my body and only one and three quarters boobs.”

Karl caught on and his eyes filled with his usual empathy.

“So I asked myself who might feel even more betrayed by Julie’s con than me?”

I could see Karl putting the pieces together after the fact.

“Someone who has been through it all and maybe worse. THREE TIMES!” I said.

“Someone you placed at the scene right before the murder,” Karl specified.

“Who had access to gowns and caps and masks, and lockers and change rooms just around the corner?”

“Well done. You pointed us in the right direction all right.” Karl said, “The murderer happens to be a former military medic. A veteran.”

I bowed my head.

I recalled the senior, now a killer, I was talking to in the Radiation Patient Waiting Room that day before I went in for my own treatment. The radiation burns on his face and neck, and the jaunty cap that distracted from but could not conceal…his mangled ear.

— ♦♦♦ —

END

Next Week: Any Day…Any Minute…Any Second

Next Week: Any Day…Any Minute…Any Second

By Bill Blick, Art by Bradley K. McDevitt

Next week, we’ll feature “Any day…Any Minute…Any Second”. Sal Gaggagio and his boys knew what he’d been up to. They knew he’d been skimming. He had to admit that he knew somehow he’d get caught. Guess was a passive suicidal thing. But now here this thing is upon him. Any day…any minute… any second. There’s a banging at the door. Don’t miss this tale of a man awaiting his fate!