Story by Lee Blevins

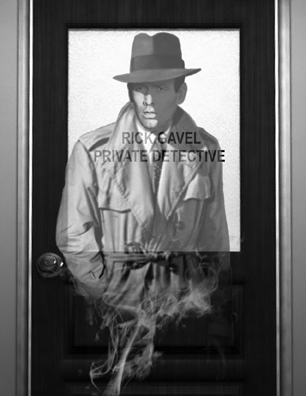

Illustration by John Waltrip

The dame walked in like she owed each step she stepped some time. She was brunette with high cheeks and low eyelids. She wore a black dress, taut, with white buttons down the front of it. Her legs were dynamite before it was invented.

I didn’t mind it much, the view.

“Are the detective?” she asked.

I wiped the imprint the back of my shoe had scuffed onto the desktop and said, “I’m the dick, alright.”

“I’m Mrs. Howie Vaughn.” Her thin eyebrows peaked this side of polite. “You’ve heard of my husband?”

I had, of course, but I’m contrary sometimes. Especially when someone raises a body part at me.

“Don’t remember if I did,” I said, gesturing for her to take a seat across from me. She was kind enough to do so, and cross her legs for me, too.

“He’s a bandleader,” she said. “Jazz.”

I lit myself a cigarette.

“I’m a blues man, myself.”

I held the crumpled pack out to her but she shook her head and said, “I believe he’s stepping out on me.”

I dropped my cigarettes and picked up my elbows and said, “Most men are whose women walk in here.”

“He’s been practicing a lot. Solo. According to the band.”

I picked up my lighter and snapped it open. “They gave him up -” I snapped it shut. “Like that?”

She allowed herself a bitter smile. “I found a dumb one and asked smart.”

I sat back in my chair and stared over her head at my name on the door and what the door said I did. It didn’t mention divorce work but, then again, it didn’t need to. It was the only reason I had a door with my name on it in the first place.

“You want proof,” I said, “or evidence?”

“Naturally, both.”

I grinned. “Spoken like the future district attorney.”

That’s when she got self-righteous with me. They do that sometimes.

“Do you have a problem with divorce, Mr. Gavel?” She sounded like a priest asking the opposite.

“Not with the money,” I said and I shrugged to let her know I was human and knew how to move my shoulders.

Mrs. Vaughn looked down and watched me tap the ash off my cigarette. Then she looked up again so fast I almost dropped it.

“What’s your fee?” she said.

“Reasonable.” I smoked some more. I like to smoke in the middle of sentences. “What’s your name?”

“Veronica.”

I left out the wisecrack about alliteration. I had no exemption when it came to silly names. I was the guy who changed his handle from Gavelle to Gavel because it sounded judicial and looked better on a business card.

“I’ll tell you my price,” I said, “and you tell me his schedule.”

— ♦♦♦ —

Howie Vaughn looked more like a second rate English teacher than a first rate trumpet player. He was small and doughy but his face was so sharp it was almost handsome. He carried himself like a suitcase on a cross-country bus, all slumped and worn handled.

I tailed him from the old money hard times brownstone Howie shared with his ever trusting wife to a cheap hotel Eastside. It was the kind of place the vice squad would bust more often if they didn’t give it so much business.

I watched through the window as Howie paid for a room and took a key from the bellhop. Then I went into the lobby and walked past the counter like I wasn’t trespassing. I followed him down the hall, shuffling my feet a bit like a drunk or maybe a pansy.

I bent down to tie my shoelaces as Howie turned the corner. And listened. I stood again and made the end of the hall in three strides and saw Howie close the door behind him. He had the first room on the right after the bend.

I went back to the lobby and walked up to the counter. The bellhop looked at me with such a blank face I rang the little bell just to try to annoy him. He was like a wall but less likely to crumble.

I got the room across from Howie’s. The bellhop didn’t ask me any questions; he was tired of all the answers.

Then I went to my room. Flophouse rooms all look different, they don’t go in for matching sets of furniture, but they all smell the same. I could’ve sat down if I’d brought some plastic.

I stood at the door, staring through the peephole, smoking. About ten minutes passed. Then I saw a blonde woman wearing a blue dress like a bearskin rug turn the corner and knock on Howie’s door. Howie opened it quick, like most men do if a woman like that is meeting them.

“Howie, baby,” she said.

Howie wasn’t much for small talk. He pulled her in in a hurry and slammed the door shut so quick he almost ripped her dress off in the process.

I pulled my compact camera out of my jacket and hoped that Howie was as smooth with zippers as he was with a trumpet. He deserved it. He was going to pay more than he knew for his fun.

I let my cigarette fall to the floor, stomped it into the carpet with all the other stains, and settled in for the indefinite wait.

I wasn’t ready for a big guy with a bald head and a retired boxer’s chin to turn the corner and kick Howie’s door in.

The woman screamed. The big guy stormed in, pulled a revolver out of his jacket pocket, and shot one of them. Twice.

I dropped my camera and pulled out my gun and flung open the door. The big guy ran bounding towards the back exit. I looked into the room. I could just make out the foot of the bed beyond the interior wall, and the pair of men’s shoes lying spent, dead, upon it.

I went after the killer.

It was a dumb thing to do. There wasn’t any money in it.

The big guy slammed open the back door like it was a cardboard prop and went hauling freight down a back alley. He had the shoulders of a god but the stomach of a schlub and I was gaining on him – one part chain-smoker, two parts angry.

The alley ran wide but short to a squat metal warehouse with truck-bearing doors. It was property of Click Chemical Company but I didn’t notice the sign. There was no way around the warehouse, the alley ended before it did.

The killer took a backwards glance, showed me his teeth, and busted through the rear entrance. But this door was heavier and the guy had already thrown his weight around so much he fell when the door did.

I thought I had him until he stumbled to his feet like a punch-drunk fighter and took off half-running, half-stumbling across the warehouse floor.

I ran inside.

There were these oversized vats all over the place, lined up one after the other and side to side with only these narrow aisles between them. They had taps on them, chrome, like the spouts of giant tea cups. I couldn’t tell whether I was in a brewery or a chocolate factory.

A night watchman with a big mustache was sitting on a stool along the back wall, brandishing a comic book like a cudgel.

“This ain’t no place for a shootout! There’s dangerous chemicals in those tanks!”

The big guy wasn’t listening. He came to a crossroads on the factory floor and took the left.

I was turning after him when I yelled back to the night watchman, “Call the cavalry, will ya?”

We were in a maze of tanks, then, that ran for a hundred yards and swung again. I took the corner to find the big guy boxed in, breathing heavy, aiming a revolver at me. My pistol was up but not pointed back like I’d a-liked.

“Dead end,” I said.

“For you, maybe.”

I jerked my head up to my left. “That your girl back there?”

“Not anymore.”

“You shouldn’t let a little thing like first degree murder get in the way of true love.”

The big guy didn’t crack a smile. I probably wouldn’t have, either, if I was on his side of the situation.

“You’re not gonna arrest me.”

I shrugged. “I’m not even a cop.”

“Shamus, then.”

“I know a good lawyer,” I said.

Now he smiled.

“Don’t need ‘em.”

I swung my pistol up and at him but he shot first. My head exploded in burst of fire and thunder.

— ♦♦♦ —

The factory was a heap of twisted metal, broken vats, and hanging rafters. The moon shone in through the hole in the roof and fire burned in scattered corners. The whole place had gone up in smoke.

I had, too.

I didn’t have a body, not even the parts I was particularly fond of. I didn’t have a thigh to pinch or a back to pat or a pair of legs to walk out on. It felt like I was drunk and about to be sick. There were wisps of mist in my peripheral vision. I was empty, insubstantial, like most of the love I’d ever claimed.

I floated in the orange-tinted dark.

“I’m dead.” I don’t know how I spoke without a mouth or heard what I had said without ears. But I did.

I turned somehow and saw a line of fire wagons and flashing squad cars at the edge of the factory. The front wall of the place was still standing, shattered, barely hanging on. But everything behind it was broken.

The firemen had given up the water, they were letting it burn.

I swung around. It felt like swimming in a lake in the springtime. Another line of cops and firemen stood on foot in the alley I’d chased the killer down. I floated towards them.

I recognized Dale Moorcock standing at the forefront, smoking a cigar, and staring at the busted warehouse like he was studying a perp. A patrolman I didn’t recognize walked up to him, all high energy and dutiful.

“Moorcock?”

“Yeah.”

I floated up over past them like I was raising my head to check the time.

“They say everyone’s accounted for.” The patrolman sounded as excited to be there as he looked. “Whoever ran after him wasn’t no cop.”

I heard Moorcock, muffled by other voices and ebbing flames, go, “Smells like gumshoe to me.”

I flew, slow, real slow, past the cluster of cops and firemen and johns who had found something even better to pass their time with towards the hotel. The back door was held open by a brick. It looked uneven now that the big guy was done with it.

I floated into the hallway. Another cop stood in front of Howie’s room, smoking. He turned his head towards me.

“Huh,” he said.

I rose upwards and flattened myself against the ceiling. It almost was like stretching, those rare times I do that by mistake. I made my way across the ceiling and dipped under the top of the door frame and into the hotel room.

The coroner and a couple boys from forensics were still going over the place. Howie Vaughn was dead on the bed with a bullet in his stomach and another in his neck. His pants were undone. The woman was gone.

“Why didn’t he shoot her?” I asked myself.

The coroner swung his head around and asked, “What?”

I flew out the open window onto the street below. Traffic moved as usual but a few pedestrians loitered around watching the theatrics. I rose higher and higher until I was flying across the street like a drunk pigeon.

I was still around but I sure was different. I was made of smoke for one thing. I could float and I could stretch and I was pretty sure that people could see me. They could hear me, too. That part didn’t make any kind of sense.

I floated across the city and towards my office building, watching the cars and the people below, heading this place and the other for booze, broads, and dough. I was almost filled with emotion and then I saw a fender bender devolve into a fistfight and remembered what kind of spot I was in.

My office was on the second floor of an old government building just north of downtown. The front door was always unlocked but I had to wait a while for someone to come out and open it. I managed to slide in and then I floated up the stairs and down the hallway to the door marked Rick Gavel, Private Detective.

That was mine, alright. I just didn’t know how to get in.

I tried the keyhole and sure enough I slid through it like I was putting a turtleneck on a giraffe.

Then I floated above my desk for a while. I didn’t have anything better to do.

I would’ve killed for a cigarette. By suffocation, I guess. I could just imagine putting one to my lips. I’d pull my lighter out of my pocket and raise up my thumb and flick it. I even heard the sound.

It was like taking a cold splash of billy club.

One minute I was floating above my chair and the next minute I was sitting in it. I had to land first, and that hurt my tailbone, but that was alright by me. I raised a hand to my head and found out I still had my fedora on. I was dressed, too. There weren’t even any new burn holes in my jacket.

“What the h—?” I asked myself.

I patted underneath my arm and sure enough my holster was still there. But it was empty. I must’ve dropped the gun in the explosion. Naturally, I kept a spare in my desk. My keys were still in my pocket.

I had my cigarette, after all. I was staring down its barrel, thumb over the lighter’s ignition, when I remembered the last thing I had thought of before finding myself man again: striking a lighter. So I struck the lighter.

Nothing happened except I lit my cigarette.

I put the lighter back in my pocket and, still trying to force it all into some kind of semblance of order, imagined the moments before I had changed. I was above the desk, dying for a cigarette. I had thought of the cigarette, the lighter. I had made a mental movie of me striking the lighter.

And I was floating above my chair again. I had a headache to boot.

“Son of a b—-.”

I formed another thought-image of myself striking the lighter and then again I was sitting in the chair, cigarette dangling from my lip.

I’m a detective. Have been for the better part of a decade. I put two and two together.

Eventually.

If I imagined striking my lighter, I would turn into smoke. If I thought of doing it again, I would return to normal. It was a mental trigger and even though I hadn’t studied psychology much, I knew how to pull a trigger.

It was all too pulpy for me.

So I went out and got drunk but serious. I managed to eat a little, too. It was about dawn when I stumbled back into the office and passed out in the sorry excuse of a bedroom I kept in the back.

I woke up hours later like a vampire after blood, except I didn’t drink blood, I drank more whiskey. I had to test my imaginary lighter to make sure it still worked in the harsh heat of high noon.

It worked, alright. Like a guy on the breadline given a big break.

Once I turned myself back into two legs, two arms, and a hangover, I asked myself some questions. I couldn’t wrap my head around the smoke stuff, so I stuck to what I had dealt with before and would deal with again.

Murder, I mean.

— ♦♦♦ —

Dale Moorcock had left me a note under my windshield wiper. My car was still parked across from the hotel and business looked to be back to usual. I had walked past the taped off remnants of the warehouse before I circled back. It looked like a bomb had fallen in the daylight.

The note said: Call me sometime. It was either that or Veronica Vaughn and I didn’t want to have that conversation just yet.

Moorcock met me at our usual place: a dingy diner uptown where they slung hash well enough to feed us and poor enough not to have too many other customers. He looked like he hadn’t been awake in a day or two.

“I figured you were wrapped up in this,” Moorcock said, “the second I saw your car parked there. I’m glad you didn’t go the big blam.”

I set down my coffee. “I was tailing the stiff. Divorce job. That woman he was seeing, what happened with her?”

Moorcock hocked up something but was polite enough to swallow it. “She’s all tore up. Tends to be the case when your husband kills your lover and then blows himself to pieces.”

“Tell me about them.”

They were Ellie and Gus Baumgartner. Gus used to be a boxer but he had taken one too many punches to the head and turned mechanic. Ellie was a chorus girl on the Borscht Belt circuit. I could’ve guessed the rest.

“How did you get out, anyway?”

“By the sole of my shoes,” I said.

Moorcock left it barely answered. “Lucky you did. That place went up like the Hindenburg.”

I lit another cigarette. “Do you know what was in those vats?”

Moorcock shrugged. His shoulders were oddly pointed for a man that large. “I don’t know the science. Some kind of government contract. Hush hush. The owner tried to put the blame on me. I told him it wasn’t my fault he hired a coward for a night watchman.”

“Or didn’t reinforce the door,” I offered.

The waitress, a woman who for all the dirt in the world still had a game set of lips, brought our food. We ate it as best we could.

“The widow Vaughn took it well enough,” Moorcock said, between choking fits.

“I bet she did.”

He sat his burger down and said, neutral as Switzerland during the last war, “You thinking something?”

“Can I get Ellie Baumgartner’s address?”

Moorcock nodded, barely, like he was planting a piece on someone. “You’re gonna stir up trouble.”

I shook my head.

“You just tend to want answers when you almost explode.”

— ♦♦♦ —

Ellie Baumgartner was in the sort of stupefied state where she would’ve opened the door for a debt collector. Some days I don’t consider myself much better.

“Yeah?” All the squeak was gone from her voice. It had been replaced by rasp and sorrow.

“Ellen Baumgartner?”

She said, soft, “Ellie.”

I handed her my card. “I’m a private detective. Named Sam Gavel. On the way over, I thought up all sorts of stories to spin ya. But I wanna lay it straight. I’m all wrapped up in that business with Howie and your husband.”

She didn’t slam the door. She let me in instead. The Baumgartner’s lived on the third floor of a nicer shade of tenement. It looked like Ellie had done her best to make the place look like a magazine picture straight out of Iowa. I expected a dairy cow to wander by.

She pointed me a chair by the radio and asked if I wanted anything to drink. I abstained for once. She sat down on the couch against the back wall and lit herself a cigarette. I had left mine in the car but didn’t have the nerve to bum one from her.

She looked at me once she had grown a nice thick ash on her cigarette. “Who hired you?” she asked.

I told her most everything but I cut down a little bit on the wordplay before Gus blew up the warehouse. Just so she wouldn’t know how desperate we were at the end.

“I don’t know why he went and done a thing like that,” she said.

“You must’ve thought it would hurt a little.”

Ellie shot me a grenade of a glance. “I didn’t shoot nobody when he did it to me.”

I smiled. “Men are funny like that.”

Ellie’s lip twitched. “I know I shouldn’t, mister, but part of me wants to spit in your eyes.”

“Part of me wishes you would.”

We sat in their room, then. Ellie had turned down the radio when she had answered the door but I could dimly hear horsemen.

“I wouldn’t have figured Veronica cared enough to hire you.”

“Did you know her?” I asked.

“Just from Howie.”

I leaned forward. “How do you think Gus found out?”

Ellie looked at me with clear eyes and a steady voice, like she was pointing out a squirrel in the park to an adult instead of a kiddo. “Somebody told him,” she said.

“Any idea who?”

Ellie shook her head and was about to back it up with words when someone knocked at the door.

“Ellie?” The man on the other side of the door sounded like he had come from the South a long time ago and almost lost his accent. “Ellie Baumgartner?”

“Who’s that?” I asked her.

“Probably police,” she said.

Ellie stood up and walked over to the door and answered it with probably the same gray expression she had answered me. The guy was barely taller or wider than her. His hat just poked over her hair.

She stepped backwards when he shot her, and he had walked away before she fell to the carpet. She had one big hole in her forehead. She looked resigned to the matter.

I turned into smoke and flew, faster than I had flown before, across the room and over the woman and down the hallway. The little guy hit the stairwell. I slipped in after him before the door slammed shut.

He kept his head down and his right hand in his coat pocket and he didn’t look back. He stepped fast but with precision. Everything about the way he moved said he had done that, or almost, before.

I floated down after, turning where he turned, and telling myself I shouldn’t become flesh and fist and beat him to death.

The little guy stepped out onto the street and got into a beat up jalopy parked in front of the tenement next door. I slid through the cracked rear passenger door window and hunkered down in the floorboard. It was pretty clean for the floorboard of a hired gun.

The little guy drove, for half an hour, at least, careful. I watched the buildings through the window diminish from tall tenements to squat storefronts to spaced out houses and I heard the chorus of sounds outside change from car horns to birds and kids.

He parked underneath a shade tree. I waited till he was walking around the car to get out, too. He crossed a cute little street towards the kind of house a successful clown might buy for his retirement. He let himself in.

I flew through the keyhole after him.

The lights were off and the curtain was closed. The place was as neat as his floorboard had been; all end tables, bookshelves, and turn of the century chairs. The little guy hung his hat on a hat rack next to a gun belt and went into the kitchen.

He turned on the overhead light and poured himself a glass of water. Then he sat down at a table beneath a window that looked out over the backyard. He popped his back against the chair. It was like so many muffled bullets.

I floated into the kitchen and hovered underneath the empty door frame.

“Who hired you?” I asked, trying to make my voice boom.

The little guy was quick. He drew his gun from his coat pocket like he was a western movie star. His eyes locked on me at once. Then, confused because I looked like a plume of smoke, they darted around some.

“Who’s there?” he asked.

“Killer,” I said, playing real melodramatic, “you’ll pay for your sin.”

The little guy sprang up, knocking his chair back, and stepped into the corner by the icebox. He held his gun pointed below me but raised his eyes back towards the smoke.

“What are you?” he asked. “Some kind of magician?”

I floated forward. The little guy’s eyes went big and his gun barrel went up. I didn’t really think about what I was saying, I just tried to make it big enough.

“I am the Smoke. I see crime wherever it strikes and punish evildoers with my ghostly might. You can’t escape me and you can’t kill what is already dead. Confess. Or die.”

The bastard smiled.

“I don’t know who you are or how you’re doing that, but you’ve got the wrong idea. I’m innocent.”

Then he darted forward, like a hound after a chipmunk, passed beneath me, and spun out past the door frame with his gun out. I was surprised he didn’t shoot the pictures off the wall.

So I turned man again and slammed him hard in the head.

The little guy staggered forward, but didn’t drop, and spun his gun around firing. I’d already turned smoke. The bullets passed through me and slammed into the icebox.

I flew around him, pulling myself over his face like I was spreading my fingers, and went regular once more. I pushed him hard and this time he fell to the floor. He didn’t let go of the gun until I stomped his hand hard and dug my heel in.

I kicked him in the face a couple times, really more like half a dozen, until he blacked out.

I scooted the gun across the floor and searched him for any backups. He had one stuffed by his right ankle. I pulled out a white handkerchief from my back pocket and used it to lift both guns and put them in the icebox.

Then I dragged him to a chair and put his hands behind his backs and cuffed him. I went digging through the kitchen drawers until I found some loose rope. I tied his feet together, too, and then I tied the rope to the handcuffs. It wouldn’t take Houdini to get out of it but I wasn’t going to give him the time for any escape plays.

Then I pulled his wallet out. His name, or his alias, anyway, was Charles Wells. He was from St. Louis, maybe.

I started to worry he wouldn’t wake up for a while. Sometimes you knock a guy out and he stays out for hours. Sometimes you knock a guy out and he stays out forever.

But assuming he would, I realized I didn’t want him to see my face. In case he didn’t like too much what I wound up doing to him. So I tied my white handkerchief around the bottom of my nose, draped over my mouth, like a bandit or a stick-up kid.

He was out long enough that when he finally came to I had what I wanted to say planned out.

“So you don’t believe in ghosts, Charlie?” I wasn’t trying to be scary or theatrical now. Just straight. “Do you believe in broken bones?”

Then I showed him the claw hammer I had found.

— ♦♦♦ —

I waited until after Veronica Vaughn poured herself a drink before I stepped out from the shadows. She had been gone for hours and she had let herself back into her apartment with the finesse of a French bulldog.

“You should’ve let it go,” I said. “You would’ve got away with it.”

Veronica glanced over at me with barely raised eyebrows and slightly pressed cheeks. Then she said, “Away with what?”

I raised a finger and pushed the brim of my hat up a bit.

“Murder.”

She looked down at the bar and finished stirring her drink. She laid the straw aside and picked up her glass and turned.

“You have the wrong idea, Mr. Gavel.” She sipped it slow enough.

I smiled. I couldn’t help it. “You told Gus Baumgartner his wife was stepping out on him. Even told him where she’d be. You found that out on your own. You figured he’d kill ‘em both but he didn’t. So you hired someone else to bump off Ellie.”

Veronica stared at me with high yet clear eyes, holding her glass still like a wood carving.

“I couldn’t figure why you hired me,” I said. “Then I realized I was insurance, the trump card that showed you suspected something but didn’t know for sure. Why would you get a private detective to find out something you already knew?”

She let me finish but she didn’t let it linger.

“That’s outlandish. A morbid theory.” She raised the glass to her lips but didn’t drink until she added, “Unfair as hell.”

“It’s the truth.”

Veronica walked over to a plush white chair with an angled back and fell down on it real graceful like. She didn’t cross her legs; she sat there with her knees pressed together. She looked up at me.

“You’re a very bad detective,” she said. “Where’s your proof?”

I spoke slow so she’d catch it all and arrange it right.

“Charlie Wells turned himself in twenty minutes ago. He put the pin on you for Ellie Baumgartner. The homicide boys will figure out the rest.”

That surprised her. I could tell because the glass shook in her hand. But only once. She was steady, the dame.

“I don’t know anybody named Charlie.”

“He knows you.”

Veronica stood up like a school teacher who has had her class interrupted for the last time. She only leaned a little.

“You’re trespassing.” She could bark like a bulldog, too.

“I’m leaving,” I said.

Then I walked past Veronica Vaughn and let myself out of her apartment. I looked back at her as I closed the door behind me. The strangle went out of her eyes.

— ♦♦♦ —

I hung around the end of hallway near the elevator until the police showed up. I stayed in smoke form so as not to complicate things or spook the elevator operator. Veronica never made a break for it; she was smart enough not to believe it. It was the wrong move that time but would’ve been the right move most.

Dale Moorcock and a couple patrolmen arrested her. Moorcock acted as polite as I’d ever seen him. He even called her miss. They don’t handcuff women like Veronica Vaughn, they just lead them down to the squad car like they had too much to drink and embarrassed the guy footing the bill.

I didn’t follow them down to the station. I was tired of playing the peep. I flew into an alley and turned man again and drove back to my office building. I stopped at the bar first.

The next day Dale Moorcock paid me a visit. He looked especially well rested. He sat down in the chair across from me and pulled a bottle of whiskey out of his pocket and set it on the edge of my desk.

“What I can’t figure,” he said, “is why Wells turned himself in without saying your name. He’s got to know that might scare the D.A., what you done to him to get him to do that. Did you tell him you’d murder him if he squealed?”

“That would be unethical,” I said.

Moorcock tapped his fingers on the arm of the chair. For such a slob he always had immaculate nails. “The real question, why would he believe ya?”

I let it spread and while it felt out the corners of the room I lit myself a cigarette. Then I asked him, “Will it stick?”

“Think so. She paid him in part with a ring. We traced that back proper. She’ll do some time.”

“Too bad she’s a woman.”

Moorcock picked up the whiskey. “Too bad.” He screwed off the top and had him a swig.

“Did you ever hear anything else?” I asked. “About what was in those vats?”

I noticed Moorcock’s sideburns were getting grayer as he shook his head. “Wouldn’t say. Top secret. National defense stuff. I get the impression they don’t want anyone nosing around, asking questions. I told ‘em I don’t know why anybody would.”

He held the whiskey out to me and said, “I lied, didn’t I?”

I had the drink and then another and then I passed it back. He caught up with me and then some.

I took another drag off my cigarette, mulled the smoke over, and said, “Let me tell you a ghost story.”

— ♦♦♦ —

END

Next Week:

A Woman Walks In. By Kat Clay, Art by Jihane Mossalim

A Woman Walks In. By Kat Clay, Art by Jihane Mossalim

Next week we are going to have a story that pretty much is the sum of “noir”. “A Woman Walks In” is by Kat Clay. Told from the viewpoint of a pulp noir dame, Clay perfectly captures the essence of noir with a line like …’ I’m a knife in the heart and a stab in the back.” If you don’t know what pulp noir is…you gotta read this! Be sure to check it out next week.