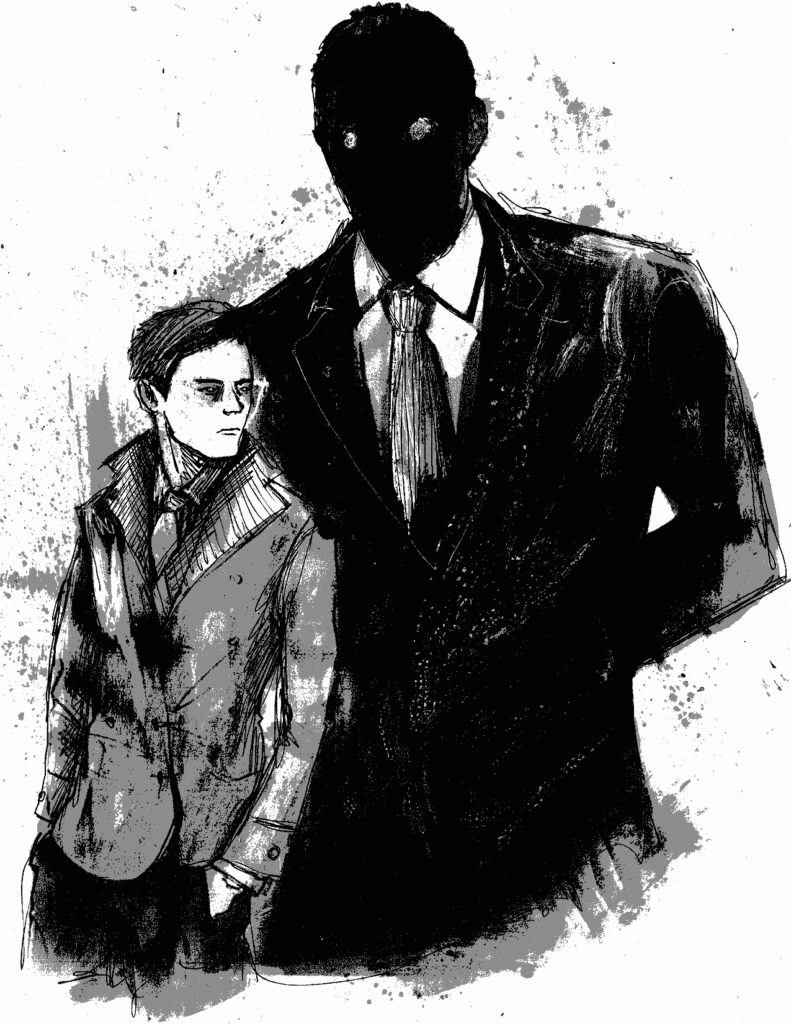

By A. S. Worth / Illustration by L.A. Spooner

For the third time in as many minutes, Edmund Hartley pressed irritably at the call-button on the wall (artfully made to resemble an acorn, the better to harmonize with the oak-leaf motif of the paper). Then, sighing with exasperation, he selected a necktie of crimson silk from the rack and returned to his dressing-table.

Another half a minute passed before, at last, the door behind him opened.

Without taking his eyes from the intricate knot which his slender fingers were busy tying in the mirror, Hartley murmured:

“I say, Malone, is it too much to ask one of your race to refrain from plundering my liquor cabinet while I am actually in the house?

“Now then, if the car is ready I—eh? Who the devil are you?”

Hartley had turned round, and now stood frowning at a stranger framed in the doorway: a tall, broad-shouldered man, dressed in a dun-colored suit of cheap make.

“Your driver’s indisposed—no, not with booze,” said the man, grinning broadly. “A little tap on the noggin, is all. But maybe I oughta take offense on his behalf, being half a Hibernian myself.” He stepped into the room with disconcerting assurance. “Anyway, I’ll be driving you tonight, kid, so you might as well finish dressing.” As the man spoke, his eyes roved about the room with seeming purpose. “Just a light jacket, I think. It’s damn hot out tonight, even for July.

“‘Course,” he added with a mysterious wink at Hartley, who only gaped at him, “it’ll be August in just a few hours, won’t it? Say, what’s this?” The man strode to the settee in the corner, on which a large cardboard box rested. “Maybe there’s something suitable in here.”

The man took off the lid, reached inside, and took out a white garment, which he let fall to its full length.

It was a gown or robe of diaphanous muslin, open at the breast. Along its long, bell-shaped sleeves were embroidered rows of curving, crimson characters, vaguely Arabic in appearance.

The man whistled.

“Say! Who says we New Yorkers got you Boston mugs beat in the fashion game? I’ve never seen threads like these in the Apple, that’s for sure.”

Chuckling, the man tossed the garment carelessly onto the settee and began to rummage in the box again.

To this point sheer astonishment had rendered Hartley speechless; now, however, he found his voice.

“I shall be inexpressibly grateful,” he said in tones of ice, “if you will refrain from handling the items in that box. If robbery is your object, you will find things of far greater monetary value in—”

Hartley broke off, visibly shuddering. The man had taken out a large bronze amulet, which he was slowly swinging back and forth by its chain, his grin broader than ever.

Hartley drew himself up to his full height, and said, with great dignity: “I do not expect a coarse-fibered man such as yourself to understand, but those are sacred things.”

“All right, kid,” said the man, dropping a vizard of black velvet back in the box and closing it again. “But however coarse my fibers may be, I’m not here to rob you, Hartley. I’m here to put you wise about a few things.

“And maybe,” he went on, producing a reporter’s notebook from his pocket and paging slowly through it, “maybe I understand more than you think.”

Hartley frowned. “You obviously know my name, to begin with.”

“Sure,” returned the man, pressing a thick finger against a page of the notebook and reading:

“Edmund Alsott Hartley, born 1905, age twenty-seven. Residence, Newbury Street, Boston, Mass. Mother: Vivian Lathom Endicott, Beacon Hill—old money. Father: William Pepperell Hartley, publishing magnate—new money. Profession: loafer, amateur poet, heir to the above. A.B.—Harvard University.”

He looked up.

“That much,” he said, turning a page, “any sap can read in the newspapers. But here’s some dope you can’t get without wearing out a lot of shoe leather. Stop me, now, where I go wrong.

“Edmund Hartley, age twenty-seven.

“Coven name: Uriel.

“Coven rank: Third-Degree Acolyte of Golgoth.

“Joined Inner Circle of The Society of Outer Yuggoth, April 1931.

“Recent activities….”

The man flipped another page, stealing a glance at Hartley, whose face had gone fishbelly-white.

“On Feb. the second of this year, approximately midnight to three A.M., ritual sacrifice of various livestock, with unknown accomplices, Provincetown, Cape Cod, Mass.

“On May the first of this year, approximately midnight to two-thirty A.M., ritual activity involving large wooden idol, in Uxbridge, Mass. Accomplices masked, presumed same as above.

“Last Friday night—”

Hartley, crimson-faced now, cried out: “Why, you dirty spy!” Then, biting thoughtfully at his thumb: “I knew I saw someone hiding in the dune-grass during the Tholish Rite—but that ass Huntington didn’t believe me….”

His eyes narrowed.

“My father sent you, I suppose,” he said coldly. “You’re another of those Pinkerton men.” He struck a splendid pose. “Well, you can tell him that a thousand Pinkertons—nay, a million—will never deter me from the path I have chosen.”

The man held up a deprecating hand. “Munsen Investigations, Inc. is strictly a one-man operation,” he said, “and you’re looking at it. But sure, your pop hired me. He’s worried about you, kid.”

Hartley sneered: “Embarrassed, you mean.”

Munsen shrugged. “Have it your way. Either way, I’ve got a proposition for you.”

Hartley snorted.

“Hear me out, kid. I bet you’d like your old man to leave you and your pals alone for keeps, right? Well then, here’s a straight deal: you come with me tonight. Then, after seeing what I’ve got to show you, if you don’t scamper right back here and flush those swell togs down the john, then I’ll go straight to Hartley Senior and tell him you’re a hopeless case. Plus, I’ll tell all my pals in the shamus biz to steer clear of the whole Hartley clan. What d’you say?”

Then, seeing Hartley’s skeptical frown, he continued:

“Hell, kid, you can probably make it to your shindy in time for the big finish, if you’ve still got a mind to go. I’ll drive you myself. It’s in Ipswich, right? Well, we won’t be more than a stone’s-throw away from there. Fifteen miles at the most.”

Hartley raised an eyebrow. “Indeed? Where then do you propose to take me?”

“Arkham,” replied Munsen. “The Misko-Whoozis University.”

Now both of Hartley’s eyebrows went up.

On the drive north, little was said: Munsen hummed tunelessly under his breath, while Hartley smoked and stared out the window and tried to look bored. But he could not conceal his excitement when the sagging gambrel roofs of the ancient city came into view, silhouetted against the stars; and when Munsen’s old Packard came to a stop in the shadow of the immense university library, it was Hartley’s foot that first touched the grass of the quad.

In silence the two men mounted the marble steps under the library portico. There the detective produced a tool resembling an awl or icepick from his pocket, and inserted its needle-end into the keyhole of one of the massive double doors. After five or six wriggling thrusts, there was a soft click. Munsen pushed the door open, took out a pocket flashlight, and led the way into the darkened foyer.

The two men made their way through the great reading-room, where the moonlight fell in long broken shafts upon rows of wooden tables and walls crowded with ancient volumes, then down a long, winding corridor.

“Stop, you fool,” hissed Hartley, tugging at the other man’s sleeve. “We are going the wrong way. It is back there, near the Head Librarian’s office. On four occasions I have tried to consult it. They—”

“Pipe down,” whispered the detective, stopping in front of what looked like a broom closet. Another vigorous application of the awl-icepick thing, and this door too swung open.

“This way, kid,” said the detective, pocketing the flashlight. Hartley followed him into darkness, down a short, narrow flight of stairs.

At the bottom, Munsen pressed a wall switch and a large room appeared, in which the most striking feature was an assortment of machines of various sizes and shapes, with great frames of wood and steel. To some of these, a wheel or a lever of black iron was appended.

“Why, it’s the library bindery,” said Hartley with a little snort. “Where volumes are repaired, rebound, and the like. Not much mystery here, I’m afraid; though I can see how the place might look a bit queer to an illitera—great Yog-Sothoth’s sapient globes!” he cried suddenly, hastening to the far side of the room.

There, beneath a wall-rack filled with brass book-binding tools, was a long table covered with stacks of ancient-looking volumes.

“It can’t be,” Hartley whispered. “Is that—O ye dark gods, it is—the Book of Iod, in Polyeucte’s Old-Occitan version!”

With trembling hands he lifted the topmost tome of one of the tallest book-towers and cradled it reverently—only to toss it aside with a strangled squeal a moment later, upon seeing what lay beneath.

“The Unaussprechlichen Kulten,” he croaked, almost inaudibly, picking up and caressing a thick volume with disintegrating leather covers.

And in this manner he made his way down the stack, in an ecstasy of discovery, crying out the name of each book in turn.

But when he saw what lay at the bottom of the pile he dropped to his knees with a faint moan and made babbling, incoherent obeisance before the table.

“Say, what’s the matter?” Munsen ambled over, a stack of books under each arm. “Don’t tell me you got yourself a defective Necro-whatzit? Well, don’t worry, son,” he went on with a grin, letting the books fall thudding to the floor. “There’s an iron-clad, no-questions-asked exchange policy at this establishment. Just take your pick of these.”

Still kneeling, his face now wearing an expression of utter astonishment, Hartley gazed down at the volumes lying in disorder on the damp concrete.

Slowly he took up each in turn, hardly knowing whether he was awake or dreaming.

Here were at least a score of copies, in half-a-dozen tongues, of the precious book of which, he had been given to understand, there was the most extreme dearth—a book into which, despite numerous and persistent acts of bribery and deception, he had been permitted to examine only the tiniest portion.

The editions he now tremblingly examined exhibited wildly divergent degrees of completeness, damage, and decay. Their multifarious typefaces and printing styles alone bespoke half a millennium at least of publication history.

“I don’t understand,” stammered Hartley at last. “I don’t understand this at all. These can’t all be…I was told there were only six…eight at the outside…on this planet at least.” He looked up imploringly at the detective. “And what about those other titles—how many….” He trailed off.

Munsen half-helped, half-dragged the younger man to his feet.

“C’mon, kid,” he said, with something like pity in his gruff voice, as he led the unresisting Hartley to a hulking piece of machinery that stood nearby. “I said I’d put you wise. I didn’t say it’d be a comfortable feeling.”

Hartley found himself blinking in silent astonishment at a large cylinder covered with inked type. On a tray before it rested a folio-sized sheet of paper, on which alternating lines of dialogue had been printed in an archaic typeface. It might have been a page of Shakespeare, save for the fact that the paper was new and the printing fresh.

“Say, is that a play? You wouldn’t believe it now, but I was aces on the stage as a kid in school,” Munsen said jocosely, peering down over Hartley’s shoulder. “Here, you read ‘Camilla’s’ part, and I’ll be this ‘Cassilda’ dame….”

But Hartley appeared not to hear him.

“I don’t understand,” he said again, in a stricken whisper. “This is a—a printing press.”

He staggered then, as in a nightmare, from machine to machine, table to table, gazing with horror upon boxes of type, drums of ink, pots of glue, jars of pigment….

On one desk Hartley found envelopes, postal stamps, and packing material, as well as a Wheelex rotary file (open to an index card showing the address for the National Library, Buenos Ayres)….

Whirling round, his face a mask of anguish, he pointed at the books lying on the cellar floor. “Those are fakes, then? All of them? B-but surely—surely the copy upstairs—”

Munsen sighed. “Grow up, kid, willya? Trust me, they’re fakes all the way down. The first thing I did, I snipped a piece off the dingus at Harvard and had the paper tested. It—hukkhhh—”

The detective’s words—and his breath—were suddenly cut off, as, silently and swiftly—too swiftly for Hartley to warn him—a panel in the wall behind Munsen slid open, and an enormous man squeezed through and placed him in a murderous choke-hold.

The detective, emitting faint wheezing sounds, beat helplessly at the brute’s monstrous forearm. Hartley raced over and tried to help, but he was quite useless, and then Munsen was pressing something into his hands—

Hartley staggered back a few paces, fumbling with the pistol, then fired wildly…and before the deafening reports had ceased to ring in his ears, two men lay dead on the floor: one shot through the heart, the other with a broken neck.

Hartley stood panting a minute, bent to examine poor Munsen, and, shaking his head slowly, stood again. For some time he stared frowning at the aperture through which the brutish guardian of the place had come.

Finally, curiosity mastered fear, and Hartley plunged down another darkened stairway, only to find himself in the doorway of an even larger room, with walls of rough stone and a few bare light bulbs hanging from a cavern-like ceiling.

In the center of the room, seated around a long, steel-surfaced table, were ten or twelve men, who turned as one to peer at the interloper in their midst.

They were by no means exactly identical in appearance, but the differences between them only served to reaffirm an initial impression that they represented minor variations of a single type. All were exceedingly pale, and of sepulchral leanness. They wore suits of black, or gray, or something in between. Nearly all wore wire-rimmed spectacles.

“Where is Hodgson? That’s not Hodgson,” cried one of the seated figures (white-maned, clean-shaven), in a high, querulous voice. “What has this dandified fellow done with Hodgson?”

“Shot him, it would appear,” murmured another.

“Well, you may as well come in,” snapped a third, and after a moment’s hesitation Hartley stepped into the room, instinctively clutching the gun. He stared in astonishment at the strange, subterranean gathering, then cried:

“Who are you? And what is the meaning of that—that forger’s workshop above?”

A hollow-cheeked man seated in the center of the table pushed his spectacles higher on his nose with a long, crooked finger. Then he said, in a peculiarly resonant voice:

“As you are the intruder here, simple etiquette would seem to dictate that you identify yourself first. But as you have us at an obvious disadvantage”—though in truth neither he, nor any of his fellows, seemed much concerned about the gun in Hartley’s hand—“I have no objection to telling you that we are the librarians of Miskatonic.

“To your second question I must reply with a query of my own, to wit: What business is it of yours? Or, to put it more bluntly, in the idiom of the day: What’s it to you?”

“What—business?” Hartley almost shrieked. “If you knew how many months—no, years—I’ve wasted…how many thousands of dollars I’ve spent…how many smirks and jeers I’ve endured at the Club….”

He began to pace restlessly back and forth.

“And now, to learn it’s all a fraud—a gigantic hoax. My God, what a fool I’ve been. And to think that my father was right all this time, damn him….”

Hartley stopped suddenly, turned to face the table once more, and shouted, waggling the gun in angry emphasis: “And you dare ask what business it is of mine?”

“Why, he’s one of the Omphalos men,” said one of the seated men, in mild surprise. “I’ve never actually seen one before.”

The figures around the table leaned forward slightly, looking at Hartley with new interest.

“Omphalos—what?” he asked, frowning.

The hollow-cheeked man directed a warning look at the man who had spoken, then said to Hartley, in a friendlier tone (though there was still something profoundly disconcerting about that queerly resonant voice): “Nothing, son—a little joke.”

With some difficulty he rose, and walked stiffly towards Hartley. “Come with me, my lad,” he said, taking him by the arm. “I want to show you something.”

The man led Hartley to a large, curtained cabinet near the table, and pulled aside the curtain to reveal a congeries of coiled wire and vacuum tubes, mingled with a few fist-sized chunks of some crystalline mineral.

“Sixteen years ago,” he said, “when I was still—er, before I retired, I was an amateur wireless enthusiast. Experimenting with thermionic tubes of my own design, I had constructed a receiver of unusual sensitivity, routinely receiving signals from locations as distant as Siberia.

“One evening, I received a series of transmissions utterly baffling with respect to both their point of origin and their lack of resemblance to any known system of human communication.

“There is no need to recount here the long process of trial and error by which I succeeded at last at understanding the rudiments of that unearthly language, and making myself understood in turn. Suffice it to say, that nothing could possibly have prepared me for the sanity-shaking bolt of astonishment that struck when I first learned that I was holding converse with beings from another dimension….”

“The Great Old Ones,” cried Hartley eagerly. “Then they are real.”

The librarian nodded gravely. “Perfectly real, I assure you.”

“And the rest of it—it’s all true as well?” Then, in a torrent of excited babble: “That even now, They sit serenely in the spaces Beyond—waiting for Their loyal servants to help Them to break though the inter-dimensional gateway? And then—They shall clear off this wretched planet like a cluttered dinner-table, and reward those who helped Them, and reign over the earth as once They did, vigintillions of years ago, when our ancestors scurried in the shadows of the great lizards and—”

He broke off. The rapturous expression faded from his face, to be replaced by a look of suspicion. “Wait a minute. Why should I believe you? I won’t be made a fool of twice.”

The librarian spread his hands. “What proofs would satisfy you? Remain with us awhile, lad. They may speak tonight, or they may not. We sit and listen.

“As an alternative,” he went on, the hint of a smile appearing on that cadaverous countenance, “you might go upstairs, to the periodical archives, and consult the obituary pages of the Arkham Advertiser and Boston Post for January twenty-fourth, 1920. My name, by the way, is Joseph Addison Wentworth. I do not think I mentioned it before. I was Head Librarian before Armitage, there.”

Hartley stared at him. “You don’t expect me to believe that you are…are….”

“Dead? To the world, certainly.” The librarian waved a hand at his colleagues. “As are eight others of our number. But to Those Beyond, organic death is merely a problem to be solved, as a school-boy solves an algebra equation. Their prodigious mechanical, biological, and chemical skill—which They have, to the extent practicable, shared with us through the dimensional aether—has enabled this imperfect extension of our existence. And upon Their arrival here, we shall enter (They have assured us) into a state of true immortality.”

“Upon Their return, you mean,” said Hartley slowly, with a slight frown.

A pause; then the frown deepened. “Come to that, none of this explains the forgeries, does it?”

The librarian looked uncomfortable.

Then another of the men at the table (whose neatly-slicked hair seemed unnaturally black) rose, approached the two men, and said:

“Oh, for God’s sake, Wentworth, tell him the whole truth.

“Listen to me, Hartley—it is Hartley, is it not? The cerebral prostheses that keep the gray matter from sloshing about too much in this old cranium sometimes produce a kind of telepathic side-effect. Everything Wentworth told you is quite true. We do indeed serve an alien race of trans-dimensional conquerors, whose aim is to break through into our own plane of existence. They mean to reshape this planet utterly, and rule it according to Their own purposes. Now, these beings exactly correspond, in every respect, to the entities you have worshipped as the ‘Great Old Ones.’ In every respect, I repeat, save one….

“They have never been here before. Indeed, They would undoubtedly be entirely ignorant of our existence at this very moment, had not my colleague happened, quite by accident, upon their aethereal communications….”

He cleared his throat. “Ergo, the, er, shared history to which you allude—the account of Their dominion in earth’s primaeval past, the prospect of Their return after ‘vigintillions of years,’ and so on—is entirely fraudulent, an elaborate fiction devised by ourselves, and circulated by means of fabricated texts and documents like those you have seen.”

Hartley said slowly, in a horrified whisper:

“D’you mean They…They just sort of stumbled upon us, like?” Then he frowned indignantly, and said: “Why, They’re just a pack of parvenus, aren’t they? Johnny-come-latelies! They—They don’t even pre-date the Wilson administration!”

He turned to the two librarians. “But why would you—? What possible purpose could you have in fostering such a monumental deception?”

The hollow-cheeked Wentworth chuckled—a hatefully gelatinous sound. “Because, Mr. Hartley, of the existence of men like you. Indeed, your reaction at this moment entirely vindicates the rationale behind Project Omphalos.”

“Omphalos,” repeated Hartley slowly. “That is Greek for ‘navel,’ is it not?” He frowned. “I seem to recall an old theological question, from my school days….”

The black-haired librarian nodded. “Baldly stated, it is this: Was Adam created with a navel—despite not having been of woman born? And if so, why might not the entire world have been created six millennia, or for that matter six minutes, ago—provided that its Creator took sufficient pains to salt the past retrospectively (as it were) with fossils, texts, memories, and other evidences of a history that never was…?”

Wentworth laid a friendly hand on Hartley’s shoulder. “The spells, the formulae in the books—that’s all persiflage, window dressing. What matters, scientifically speaking—what weakens the membrane, I mean, between Their dimension and ours—are the brain-waves, appropriately focused, of men like you: intellectual, sensitive…and, er, shall we say, suggestible?”

“It occurred to us,” the other librarian went on, “that such men were just the sort most likely to be attracted to…well, to romantic fairy tales, not to put too fine a point on it. The fantasy, for instance, of being a member of an ancient, esoteric order, possessing knowledge of a secret history dating back to the deepest abysses of time, and…well, you know the rest….”

An awkward silence ensued, during which Hartley stared dully at the floor, his face burning. It was broken at last by the querulous, white-haired man who had first spoken:

“I suppose we’ll have to kill him, then? His brain-waves will be all wrong now. And besides, he shot poor Hodgson.”

“We should leave the decision, I think, in the hands of young Hartley here,” murmured the black-haired librarian, patting him on the back. “Well? How about it, lad? Can you continue to serve Them as we do—without myths, without illusions?”

“Well, I don’t know,” murmured Hartley slowly. “That is, I….” His nose wrinkled in irritation. “Well, I mean, it’s hardly the same, is it?”

Another long, even more awkward silence.

Then a diminutive figure at one end of the table gave a diffident cough.

“If I might venture a suggestion,” he said, scratching at his thin mustache, “I believe there is a Lammas-eve gathering tonight, not far from here—in Ipswich, I think.” He cast a glance at a clock on the wall. “If you were to leave now, you might—”

“Oh, all right,” snapped Hartley. “I’m going, I’m going.” Without another word—and with very bad grace—he stalked from the room.

“They are real, Mr. Hartley. Do remember that,” one of the librarians called after him, almost apologetically.

Outside, on the library steps, Hartley paused to light a cigarette, glowering up at the star-crowded cosmos.

But before he had taken many steps in the direction of Munsen’s vehicle he threw it petulantly away, stamped an angry foot, and cried: “But it’s hardly the same, is it?”

END

Next Week:

Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas by Haynes / Illustration by Cesar Valtierra

Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas by Haynes / Illustration by Cesar Valtierra

Next week we’ll be dishing up some holiday spirit with “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” by T.G. Haynes. It’s not what you want the weekend before Christmas. The large department store just lost its Santa by way of murder. Who would ever want to do old Saint Nick in? That’s what the good detective and his partner have to find out pronto. You won’t want to miss the twist at the end of this one.